Introduction

This is part of Diamonds in the Rough, a section of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

This book is a short collection of six articles about the cinematic and literary worlds of Ian Fleming and James Bond. Both have, of course, already been covered in scores of other books, articles and documentaries, and one would be forgiven for thinking there’s no ground left to cover. But in the last few years, I’ve investigated some lesser-known, and in some cases completely unknown, facets of Ian Fleming’s world, and I hope found a few diamonds lurking in the rough. Some of the material in this book has previously been published in newspapers, magazines and online, but all of it has been revised and in some cases greatly expanded.

The opening article, Gold Dust, is about my hunt for Per Fine Ounce, the lost James Bond novel by South African thriller-writer Geoffrey Jenkins. This first appeared in issue 2 of Kiss Kiss Bang Bang magazine back in 2005, and I’ve made just a few revisions. The full draft of the book has sadly still not been found, but Jenkins’ estate published a novel with the same title by Peter Vollmer in September 2014 as a result of this story, inspired by the surviving material.

Uncut Gem builds on research I published in The Sunday Times in 2010, examining the attempts to film Ian Fleming’s non-fiction book The Diamond Smugglers. I’ve gone into a lot more detail here than in previously published versions, about the background of the book, the contents of the screenplay I unearthed, and the prolonged efforts to turn the property into a serious rival to the Bond films. John Collard’s family very kindly gave me access to a huge amount of material, including private correspondence, IDSO agents’ reports, and the complete manuscript of Collard’s book.

In Commando Bond, I look at how Ian Fleming incorporated elements of real life into his novels, and explore the numerous references and allusions to special forces. Fleming’s use of real operations had a curious cinematic echo after his death, as I explore in Black Tie Spy, an extension of an article I originally submitted to The Sunday Telegraph. The seed for my research here was planted when I was writing a novel. I’d plotted out a chapter set during the Second World War in which my protagonist, a British secret agent, is sent on a mission to an island in the Baltic. But as I came to write it, I realized I was unsure how he should reach the island. Would he have been sent by parachute? By submarine? Or some other way? I reached for one of my most thumbed books, M.R.D. Foot’s official history of the Special Operations Executive, to refresh my memory on how that organization had inserted secret agents behind enemy lines during the war. To my surprise, I found myself reading a passage I hadn’t paid sufficient notice to before, which mentioned an operation undertaken by MI6 in 1941.Those few lines took me on a fascinating journey into the origins of one of the best loved moments in modern cinema: the opening scene of Goldfinger.

For Smersh vs Smersh, I hop over to the other side of the Iron Curtain to compare the real organization of that name with the one Fleming created for his novels, tracing his research into Soviet intelligence. Who inspired Rosa Klebb and Red Grant? This is where you’ll find out.

Finally, Bourne Yesterday, first published on my website, looks at Ian Fleming’s influence on the Jason Bourne series, and the influences on his own work.

So please, grab your wetsuit and Champion harpoon gun and join me as I dive in to the world of Ian Fleming and James Bond.

Jeremy Duns

Mariehamn, December 2014

Note: this section now includes Rogue Royale and Catch-007.

Gold Dust

This is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

Geoffrey Jenkins

Since Ian Fleming’s death, a few snippets of information have cropped up that have both fascinated and frustrated Bond fans. One of these is the ‘lost novel’ Per Fine Ounce. A James Bond adventure written by a friend of Ian Fleming, the plot of which Fleming was aware of and might even have contributed to, officially commissioned by Fleming’s estate but never published... Unsurprisingly, this book has become something of an Eldorado for Bond-lovers. So what was Per Fine Ounce, exactly?

After Ian Fleming’s death in 1964, British journalist John Pearson sat down to write a biography of the creator of James Bond. Pearson set about contacting as many people he could find who had known the novelist, asking for their recollections. On 6th June 1965, he wrote to Geoffrey Jenkins, a South African who had become friends with Fleming in the 1940s, when they had both worked at The Sunday Times.

Jenkins had returned to South Africa and become a thriller-writer—his first novel, A Twist Of Sand, published in 1959, sold three million copies worldwide.1 Fleming thought highly of it—or at least valued Jenkins’ friendship enough to praise it in print: ‘Geoffrey Jenkins has the supreme gift of originality,’ he wrote in The Sunday Times. ‘A Twist of Sand is a literate, imaginative first novel in the tradition of high and original adventure.’2 In 1962, Fleming reviewed Jenkins’ third novel A Grue Of Ice, also for The Sunday Times. Comparing him favourably to John Buchan, Hammond Innes and Geoffrey Household, he concluded that Jenkins was ‘in the ranks of the great adventure writers’.3

It’s not surprising Fleming raved about Jenkins—he knew the writer, and in many ways his work was similar to his own. This was noted by other publications: Books and Bookmen felt Jenkins’ style combined ‘the best of Nevil Shute and Ian Fleming’,4 while The Times Literary Supplement wrote: ‘Ian Fleming is Geoffrey Jenkins’ spiritual headmaster and Mr Jenkins stands in the not unenviable position of being Mr Fleming’s most brilliant pupil’.5 When he received Pearson’s first letter in 1965, Fleming’s pupil had four best-sellers under his belt—he would go on to write 12 more.

On 24th September 1965, Jenkins sent an eight-page type-written reply to Pearson, in which he recounted his memories of Fleming, who he had met while he was on Lord Kemsley’s Commonwealth Scholarship scheme:

‘Later Lord Kemsley himself asked me to stay on and gave me a job in the Foreign Department, of which Fleming was the head.’6

Jenkins related how Fleming took him out to lunch early on in the job, he suspected out of duty, but that they quickly became friends: ‘In the next eighteen months or so he had introduced me to many leading London clubs.’7 According to Jenkins, Fleming was, unlike Bond, ‘essentially an introvert’; nevertheless, he was surprised, on meeting his old friend for lunch at The Caprice in London in 1961, when they had both become best-selling authors, that Fleming was full of doubts about his creation: ‘Fleming was gloomy; publishing and film worries were in his mind; he was searching for a theme for his next Bond, which was due the following spring, nine months away. “I have created a monster,” he told me. “I have written every permutation of sex and sadism, and still the public wants more? What shall I write about?”’8

The result was The Spy Who Loved Me. But despite Fleming’s dark mood, something triggered off the old spark between the two:

‘In a moment we were kicking around—in a light-hearted, gay mood, completely in contrast to that of a few minutes before—the idea of making Bond a necrophile. Both of us threw our ideas into the melting-pot as they were minted; scene after scene built up, each more hilarious than the last, each more censorious than the last, until we found that most of the afternoon was gone and that we were the only diners left, with waiters standing by in patient protest: something which had happened many times before in the Fleet Street days.’9

In the next paragraph, Jenkins drops a bombshell. A few years before the Caprice lunch, he and Fleming had kicked around ideas about Bond altogether more seriously:

‘I tried very hard to get him to come out to South Africa to write a James Bond set in this country. Twice he nearly came. I wrote him the outline of a plot which he thought had great possibilities (this was before A Twist of Sand) bringing in a secret/spy escape route through a magic lake named Fundudzi in the Northern Transvaal, towards Mozambique. “I must know how everything smells, tastes and looks for myself in South Africa,” he wrote to me. “Without them, it is not for me.” On both occasions when he decided to come and see for himself, something arose and he postponed it.’10

Jenkins goes on to discuss Fleming’s views on writing thrillers: expertise was essential, and could almost over-rule the need for a decent plot (Fleming apparently felt his own plots were thin). Jenkins says that at one of their last meetings Fleming had told him that he felt success had sapped him of energy and creativity, and also reveals that the writer’s favourite city had been Hong Kong, on account of its vibrancy.

In his covering note for the letter, Jenkins asked Pearson if his Bond outline was in Fleming’s papers, as he seemed to have mislaid it. ‘It ran to about 25 pages of typescript, and [Fleming] was pretty keen on it.’11

On 1st October 1965, Pearson replied, thanking Jenkins for his ‘splendid letter’, which he had enjoyed hugely—especially the idea of making Bond a necrophile: ‘he would have done it so well, too’. He added that he had found Jenkins’ Bond outline, and asked if he should send it to him. ‘Perhaps you should write it yourself now?’12

Unknown to Pearson, that idle comment would open up a hornet’s nest. Encouraged by Pearson’s enthusiasm, Jenkins replied to him on 6th October 1965, saying that he would appreciate seeing the outline again: ‘Ian was very keen on it, as I mentioned, and we discussed it verbally at length and made quite a few changes. I know what was in his mind for it and the approach he contemplated.’ He ended the letter by saying he would be in London in November—’perhaps we could meet?’13

The two men did meet, on 2nd November 1965; the next day, Pearson wrote to Jenkins:

‘I did enjoy meeting you last night, although I meant to buy you the whisky. You must let me do so properly before you go back to the sun.

I hope that you write that book. Just reading your synopsis through I can understand why Ian got so excited about it, and you can’t possibly allow such magnificent material to go to waste. Gold bicycle chains and baobab wood coffins. What else can the Bond-lover ask for?

All best wishes,

John Pearson.’14

Later that same November, Jenkins met with Charles Tyrrell of Glidrose Productions Limited, the corporate owners of the James Bond literary copyright and Bond film co-producer, Harry Saltzman, at Bucklersbury House in London to discuss the idea of him developing his outline into a book.15 Glidrose were already considering commissioning ‘continuation’ Bond novels,16 so a friend of Fleming’s, and a best-selling thriller-writer to boot, appearing with a plot that Fleming had apparently considered writing himself may have initially seemed like a gift. The fact that John Pearson had found the outline in Fleming’s papers proved Fleming had known about it—and had taken it seriously enough to keep it.

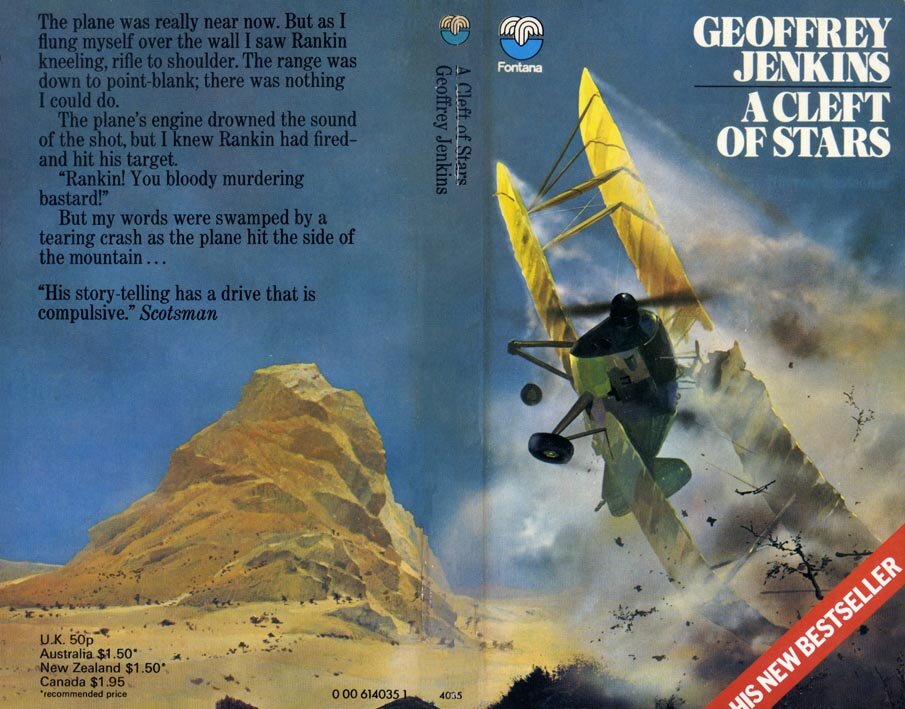

Jenkins’ ideas certainly sound like promising material for a Bond adventure. Fundudzi is a real lake in the Zoutpansberg Region of South Africa; hidden in a valley, locals believe it is sacred and enchanted. A white crocodile and a huge python are said to live in the lake, guarding its ancestral spirits. Jenkins’ 1973 novel A Cleft Of Stars is set in the region:

‘It is primarily the home of the grotesque baobab trees, whose bulbous, purple-hued trunks reel across the arid landscape like an army of drunken Falstaffs, blown and dropsied with stored water…’17

Baobab trees are also seen as sacred in many parts of Africa, and are sometimes used as coffins: the bodies of important individuals are placed in a hollowed-out baobab trunk to symbolise the communion between the forces of the plant gods and the body of the deceased.18

Precisely what Jenkins had planned for the baobab coffins and gold bicycle chains is a mystery, but his pitch must have worked: Jenkins felt that Tyrrell and Saltzman were both very keen on the idea.19

Negotiations over the contract took months. Jenkins wanted his regular publisher Collins, rather than Cape, the Bond books’ usual home; and Fleming’s widow, Ann, became perturbed about the issue of ‘the original copyright’—’whatever that means,’ Jenkins wrote.20

On 12th May 1966, Glidrose cabled Jenkins to tell him that they had agreed to grant him permission to write the book, and would get the contract drawn up with his London solicitors, Harbottle and Lewis.21 However, it wasn’t until 24th August 1966 that Harbottle and Lewis sent Jenkins a contract—and even this looks like it wasn’t the final version. The covering letter mentions that Glidrose were making noises about adding a clause stating that Jenkins would not be entitled to profits from merchandising related to any film of his novel. The contract in Jenkins’ papers is undated and unsigned, but does contain such a clause. It seems likely that in the autumn of 1966, Glidrose and Jenkins’ solicitors wrangled over the small print. The contract we have states that Jenkins would be paid £5,000 on signing the contract and £5,000 on publication of the novel. He would also be entitled to half of Glidrose’s 2.5-percent share of global profits of any film or serial adaptation (excepting merchandising). He had six months to write the manuscript, which had to be at least 65,000 words long. He was to send four copies of the finished draft to Glidrose, but there was a clause giving them the right to refuse to publish if they saw fit.22

Jenkins was not the only iron Glidrose had in the fire, however: Kingsley Amis was approached at least five months before Jenkins was sent his contract. Alarmed by several attempts to publish unlicensed Bond novels, the estate had decided to enter the fray by commissioning an official new Bond writer, and Amis was one of the authors under consideration.23 He was an obvious candidate: as well as being one of Britain’s most respected novelists, Amis was a self-confessed “Fleming addict”. 24 Since Fleming’s death, he had proof-read The Man With The Golden Gun and published two books about Bond (The James Bond Dossier and Every Man His Own 007, the latter under the pseudonym Bill Tanner).25

Ann Fleming was ‘violently against’ the idea of a continuation novel, and of Amis writing it, but Ian’s eldest brother and Glidrose director Peter Fleming was in favour and he eventually won her round. On March 15th, 1966, he wrote a letter to her that concluded:

‘As you know, I was originally less than lukewarm towards the idea of a Continuation Bond; but, having seen more of the ramifications and repercussions of this extraordinary market, I now feel strongly that the right thing to do is to tell Kingsley Amis to go ahead.’26

According to Peter Fleming’s biographer Duff Hart-Davis, Glidrose were ‘forced’ to commission Jenkins as he had ‘claimed in a letter to the board that his would be the only true continuation, because he had written the outline of the plot (set in South Africa) at Ian’s request, and Ian had seen it and “indeed was most enthusiastic about it.”’27

This suggests that Jenkins might have been aware that he wasn’t the only writer being considered. It seems he became impatient with the amount of time it was taking for permission to be granted him, and told Glidrose he would write the book anyway. As Jenkins had letters from Fleming’s biographer praising his synopsis and confirming that it had been in Fleming’s possession, he might have been much harder to stop than the pirates the continuation idea was meant to suppress. Perhaps for this reason, Glidrose granted him permission to write the book, but kept the right to refuse publication.

When Jenkins submitted Per Fine Ounce—probably in early 1967—they exercised that right of refusal. Despite an exhaustive search of Jenkins’ papers with the help of his son David, a small army of archivists and even a psychic, nothing of the final draft of Per Fine Ounce has yet been discovered. Four pages of an earlier draft of the novel have come to light, however.

The pages are numbered 86, 87, 88 and 89. Each contains numerous handwritten corrections and additions in the margin, and has one faint diagonal pencil mark through it. Jenkins may have later decided to abandon the scene, or end it differently, or (perhaps most likely) the pages were simply typed up again with all the corrections added, a clean proof to be copied and sent to Glidrose.

The scene takes place in M’s office. Present are M, Bond and a financier called Sir Benjamin. Page 86 starts in the middle of a discussion between the three men:

‘“Expensive powder-puff—£137 millions,” said M.

Bond argued on. “This gas cylinder business wasn’t big enough to kill the pound. It was bound to be discovered. I say it was meant to be discovered…”’28

In the first page and a half, Bond argues that an incident with some gas cylinders that M and Sir Benjamin feel was designed to knock the rate of the pound was merely a smokescreen, and that some gold flights from South Africa are someone’s or some organisation’s real target. Sir Benjamin admits that if the gold flights were downed, it would ‘send sterling for the count’. Much discussion ensues about these gold flights, which are due to travel from Luanda to London via Angola and Las Palmas, helped along by CIA surveillance, American fighter planes from their base on Ascension Island and nuclear subs carrying surface-to-air missiles. ‘Finger-on-the-tit stuff,’ Bond murmurs.

Bond wants to return to South Africa (where, it seems, the cylinder incident took place), and have another look at the situation. M thinks this would be a waste his time, and refuses to authorise it—it’s ‘outside the province of the 00 Section’. Then it really heats up:

‘Bond stood up, looking down from across the desk into the old sailor’s face. “I’m sorry, sir.”

M put down his pipe. “Sorry about what, 007?” The voice was ominous.

“In just over two months, this department won’t exist,” he said. As he did so, he regretted the pain he saw in the face of the man whom he admired above anyone he knew. “You recalled me because the Treasury wanted help. Fair enough. But do you think you’ll get any more than an appreciative minute for today’s discovery? Do you really think they’ll reprieve your department because of a couple of piddling things like soda-water syphon cylinders?”

“I am ordering you, 007.” Bond heard the sharp intake of breath from Sir Benjamin behind him.

“And I,” said Bond, “Am—for once—refusing that order…”’

Bond uses an extended gambling metaphor to argue his case—there are references to chemin de fer, and ‘the click of the chips, the silver chandeliers and the quiet monotones of the croupiers’—and concludes: ‘It’s the man who has the nerve to climb in when the Casino tries to keep him away who breaks the bank’. M says that Bond has done that many times in the past and Bond says yes, he has—’But I did it for your department.’ When Sir Benjamin asks Bond if he intends to back no more than a hunch, Bond replies: ‘To the point of resigning.’

As the excerpt—and the chapter—ends, a VC10 takes off to South Africa and we learn that ‘James Bond, for the first time, was going on a mission without the blessing of M.’

The scene itself is expository—the usual Bond and M in the office set-up—and such scenes are rarely exciting. However, it’s clear from these pages that Jenkins knew Bond. This wasn’t just a friend of Ian Fleming’s who wrote thrillers—he was clearly a Bond aficionado. This is evident in Bond’s voice, the descriptions of M, and the general atmosphere. Aside from a few typos and the odd clumsy phrase, it feels like it could be an excerpt from a Fleming Bond novel. It is also ahead of its time: at least 14 years before John Gardner’s Licence Renewed, Jenkins had the idea of disbanding the Double 0 Section, and 22 years before the film Licence to Kill, Bond went rogue.

So why was the book rejected? According to Peter Janson-Smith, Ian Fleming’s literary agent and former chairman of Glidrose, Per Fine Ounce was rejected on the grounds that it wasn’t up to par. ‘Frankly,’ he says, ‘I thought it was extraordinarily badly written.’29

This seems at odds with the standard of the four draft pages and the four best-sellers Jenkins had published before 1966, two of which Ian Fleming had praised highly. ‘There was a rumour going round that Jenkins was very good at creating plots but wasn’t much of a writer, and that he had an editor at Collins who wrote his books up,’ said Janson-Smith. ‘When I read his Bond story, I could believe that rumour. It just wasn’t good enough.’

Jenkins was a close friend of his publisher Sir Billy Collins, and sometimes took advice on small points from him (in much the same way Fleming did from William Plomer), but there is no evidence in Jenkins’ notes, correspondence or drafts that Collins or anyone else was effectively writing his books on his behalf. Even if the rumour were true, Jenkins’ previous books had all been best-sellers: did nobody consider editing Per Fine Ounce in the same way? Janson-Smith said he felt no editing could have saved the novel, but added: ‘Possibly we were a little stricter with [continuation novels] in those days.’

Janson-Smith had a vague recollection that the book had had ‘something to do with gold’—and that the plot had been ‘rather good’. He said Ann Fleming had not been involved in its rejection—’she played no part in editorial decisions’. And he had one other twist to the tale: he didn’t believe that Glidrose (or Ian Fleming Publications, as the company is now called) would still have a copy of the book. ‘They would have returned it to him,’ he said firmly. This was because of the problem of plagiarism. Even while Fleming was alive, unsolicited typescripts had poured in to Glidrose—the standard practice was to return them, for fear of being sued later. As Glidrose didn’t think Jenkins’ novel was good enough to publish, Janson-Smith suggested, they would have no reason to keep it—and good reason to send it back, to help ensure that Jenkins didn’t sue them for any similarities in any subsequent continuations. ‘They would have sent a note saying the story was his to use again, but he just wouldn’t be able to use Bond, M and so on.’

Indeed, the version of the contract Glidrose sent Jenkins that is now stored in his papers included precisely such a clause:

‘If the New Bond Book offered by Glidrose for publication hereunder is rejected by Glidrose nothing herein contained shall prevent Geoffrey Jenkins from using elsewhere any part or the whole of the plot of such rejected New Bond Book and any of the characters appearing therein other than James Bond and the Bond characters.’ 30

It seems likely that Jenkins would have wanted to take Glidrose up on this. Writing a novel is no easy business, and why waste a plot you have already worked out? Many of Jenkins’ books have similarities to and echoes of Fleming’s work—could one of them be a reworked Per Fine Ounce? John Pearson was, unfortunately, unable to remember anything specific about the book, and had no firm memories of his correspondence and meeting with Jenkins in 1965.31

Some writers have speculated that the plot was about diamond-smuggling.32 This is possible but, in the draft pages at least, it is about gold. Added to this are Jenkins’ references to gold bicycle chains, Peter Janson-Smith’s vague memory of ‘something to do with gold’, and that ‘per fine ounce’ is a common abbreviation of ‘per Troy fine ounce’, the standard unit of weight for gold. The standard unit of weight for diamonds is the carat. (Carats are also used for gold; this refers to the proportion of gold in an alloy, rather than the weight, and is now spelled “karat” in some countries to avoid confusion.)33

Jenkins’ 1983 novel The Unripe Gold is about another precious metal: iridium. Set in the diamond mining town of Oranjemund in south-west Africa, it features a crazed German scientist who has discovered a ton of the extremely rare metal, which he intends to use to tip the balance of the Cold War. As in Fleming’s Thunderball, a group of terrorists masquerade as prospectors. The town is protected by a Major Rive, the head of a security service employed by Consolidated Diamond Mines.34 As a terrorist approaches the town’s perimeter fence, the guard on duty mistakes him for Rive:

‘What was bugging him tonight? Sneezer asked himself. Maybe one of his hunches—and no one could deny that on a famous occasion Major Rive’s hunch had paid off when there had been a James Bond attempt to land a plane upcoast and fly out a parcel of stolen diamonds.’35

This appears to be a reference to an incident described by Ian Fleming in The Diamond Smugglers, which coincidentally was also used as the basis for the pre-titles sequence of an unfilmed screenplay adaptation of that book by the Australian writer Jon Cleary in 1964. [And that’s the subject of the next chapter.]

In several of Jenkins’ novels, the protagonists are ruthless Brits with naval backgrounds. A Cleft Of Stars’ Guy Bowker has had commando training and served in the Royal Navy in the Second World War, while Ian Ogilvie, the hero of The Watering Place of Good Peace (1960), is a Scot who was crippled by a shark, also while in the Royal Navy. He joins an organisation constructing anti-shark barriers ‘a fast car, a pretty girl, and half a dozen drinks’ after his accident.36

The clearest echo of Bond, however, is Geoffrey Peace, the debonair and cruel-mouthed hero of A Twist Of Sand (1959) and Hunter-Killer (1966). The latter was the first novel Jenkins wrote after Fleming’s death, and includes a wry and touching tribute to his old friend.

Published a year before the release of the film You Only Live Twice, the novel’s narrator is John Garland (note the reversed initials), who was Geoffrey Peace’s first mate in A Twist of Sand. Garland has not seen Peace for years when he suddenly receives a cable from his old friend asking him to come to meet him in Mauritius. Garland is a navigational expert, and Peace says he wants to collaborate with him on a system he has devised. But when Garland arrives, he finds that Peace is distracted. He wants to sail around some remote islands in the Seychelles used by one of his ancestors, a pirate—and when he’s finished doing that, he decides to go spear-fishing. Garland is not pleased:

‘My irritation with the whole affair increased when I found that I would have to stage back to Johannesburg via East Africa, and that the aircraft was an old flying-boat which only made the leisurely trip once a week. That meant a further delay of three days in the Seychelles. I cursed the soft languor of Limuria.’

As Garland has dinner in his hotel that night, a naval officer interrupts his meal and hands him a note, which says that Peace has been found dead in the water half a mile north of Frigate Island.

All this is told in flashback as Garland looks at Peace’s coffin on board Peace’s luxury yacht in Mahé. He is grief-stricken by the loss of someone he admired so much, dismayed by the publicity surrounding his death—elaborate preparations are underway to bury Peace at sea with full naval honours—and perversely angry that Peace died ‘no more excitingly than an overfed businessman who drops dead after a dip at Ramsgate’.

Just a few pages into this novel, Jenkins made several references to both James Bond and Ian Fleming, some more obvious than others. The opening chapters are a clever spin on Fleming’s 1960 short story The Hildebrand Rarity, published in the collection For Your Eyes Only in 1960. In that story, Bond was sent to Mahé by M to see if it would be feasible for the Admiralty to relocate its fleet base there from the Maldives:

‘Bond’s report, which concluded that the only conceivable security hazard in the Seychelles lay in the beauty and ready availability of the Seychelloises, had been finished a week before and then he had nothing to do but wait for the SS Kampala to take him to Mombasa. He was thoroughly sick of the heat and the dropping palm trees and the interminable conversation about copra.’

Like Bond, Peace goes spear-fishing; like Bond, Garland is forced to while away his time waiting for the weekly boat to East Africa. In a wry touch, in Hunter-Killer the British now have a missile base in the islands.

Fleming wrote The Hildebrand Rarity after visiting the Seychelles for the Sunday Times in 1958: he searched for buried pirate treasure on Fregaté, also known as Frigate Island (the hotel he stayed in, the Northolme, now has an Ian Fleming Suite.)

The remark about Ramsgate may be a reference to Goldfinger: James Bond stayed there before playing golf with the eponymous villain at the nearby Royal St George course in Sandwich—Ian Fleming died of a heart attack shortly after a meeting there.

Few people who read Hunter-Killer at the time would have been likely to have spotted these references—they are skilfully woven into the action. But I think there is another layer to these scenes that was entirely personal to Jenkins, and which related to his Bond synopsis. He had sent that to Fleming and suggested that he come out to South Africa to research and write it—in effect proposing a business partnership. In Hunter-Killer, the situation is reversed: it is Peace/Fleming who asks Garland/Jenkins to come out to see him for business. When Peace seems more intent on having fun than collaborating, Garland sourly begins to view what had been the chance to work with an old friend as a failed ‘deal’. When Peace dies, he is racked with guilt about this. Was the opening of Hunter-Killer a metaphor for how Jenkins felt about his Bond collaboration with Fleming?

Perhaps to compensate, Jenkins said goodbye to Ian Fleming in his fiction. Garland watches Peace’s steel coffin, ‘shrouded by a tarpaulin’, fired from a British destroyer’s depth-charge mortar in the company of Peace’s former boss, the Director of Naval Intelligence. Ian Fleming, of course, had been personal assistant to the DNI in the Second World War. A helicopter then hovers over Peace’s grave and a huge wreath floats down at the end of a parachute.

Having given his newly Bonded version of Fleming this marvellous send-off, Jenkins then brings him back—and in a way that Fleming would surely have enjoyed. In the next scene, Garland visits the DNI in a cottage on Mahé, where he is living with a beautiful young Seychelloise called Adele. As the three of them talk, Garland senses someone approaching. It is, of course, Geoffrey Peace.

‘I blinked in disbelief. Peace stood on the terrace in the same black rubber suit in which I had seen him in his coffin. A long diving-knife was in his hand. I tried to speak, but the words would not come…

Mam’zelle Adele was still on my arm. Peace’s greeting to her was level, comradely.

‘Hello, Mam’zelle Adele.’

She detached herself. ‘Good evening, Commander. Was it a good trip?’

‘Get me a drink and I’ll tell you,’ he replied.’37

Over wine and turtle steak, the burial at sea is revealed to be a hoax by the DNI to persuade the US Air Force, the CIA and others that Peace is dead so he can embark on a secret mission involving a new type of space missile: ‘the ultimate weapon’. Later in the novel, Peace introduces himself as “Peace—Commander Geoffrey Peace”.

Jenkins’ novels often feature tough men scrabbling for a prize across harsh terrain—in Africa, the ocean or, particularly effectively in A Grue Of Ice (1962), Antarctica. None, however, feature Lake Fundudzi, gold flights, attempts to kill the pound or gas cylinders. Of them all, I think A Cleft Of Stars gives the best sense of what a Jenkins Bond novel might have been like. It shares an antecedent with Diamonds Are Forever: both books owe a debt to John Buchan’s 1910 adventure Prester John, which concerns the tracking down of an illicit diamond pipeline in Africa. A Cleft Of Stars, which involves both diamonds and gold, is set in precisely the same region of South Africa as Jenkins’ Bond outline from the ‘50s; the main character even spends some time hiding out in a hollowed-out baobab tree. It’s a superb thriller: the descriptions of landscape and physical discomfort—Jenkins’ trademarks—are exceptionally vivid and well drawn, and the tension builds to a highly Bond-like conclusion. Like many of Jenkins’ novels, it would make a terrific film.

Jenkins was attracted to many of the same subjects as Fleming. Natural oddities abound in his work, as in A Twist of Sand, in which two characters see a ‘double-sun’, a phenomenon that had been recorded by meteorologists in 1957. He was fascinated by real-life mysteries: Scend of The Sea involves the search for the Waratah, a ship that sank without trace in 1909. Jenkins’ villains also feel of the same stamp as Fleming’s: A Cleft Of Stars’ Doctor Manfred von Praeger keeps a hyena for a pet, while in A Grue Of Ice Carl Pirow is known as ‘The Man With The Immaculate Hand’ on account of an uncanny ability to imitate the fist of any ship’s radio transmission. Jenkins’ novels were meticulously researched, and packed with just the kind of schemes and scrapes Fleming loved. Fleming was right—Jenkins was a great adventure writer.

How to square that assessment with Glidrose’s decision not to publish? Times, and attitudes, change: due to the enormous cultural influence of Fleming’s creation, it’s easy to forget that his novels were unusually digressive, leisurely and stylised in comparison to other thrillers of the time. Geoffrey Jenkins wrote straightforward adventure novels, sometimes short on style but always long on atmosphere and suspense. In the immediate wake of Fleming’s death, it’s perhaps unsurprising that Glidrose weren’t keen—especially as a writer of the literary stature of Kingsley Amis was also interested in tackling Bond.

Richard Johnson and Honor Blackman in the 1968 adaptation of A Twist of Sand

We don’t know how Jenkins reacted to Per Fine Ounce’s rejection—his son says he was very much “a closed shop” when it came to his professional life. Jenkins continued to write best-sellers, though, and the film world soon spotted his potential: A Twist of Sand was released by United Artists in 1968, directed by Don Chaffey. Richard Johnson—who had been Terence Young’s favourite to play James Bond38—starred as Commander Geoffrey Peace, alongside Honor Blackman and Guy Doleman. Geoffrey Jenkins died in 2001, aged 81.

Could Per Fine Ounce have been a cracking Bond adventure? Jenkins’ published novels and the four draft pages strongly suggest it might have been—but it may also have needed a sensitive editor to bring in some of Fleming’s literary flair, an idea that would probably not have been attractive at the time. We might never know. David Jenkins is mystified as to why the manuscript of Per Fine Ounce is not in his father’s papers: ‘My dad kept everything.’ Indeed, his papers include notes and drafts of all his novels, newspaper clippings, maps, pamphlets, publicity material, photographs, invitations to award ceremonies and hundreds of letters—even correspondence regarding a desk he commissioned. But, aside from the four draft pages, nothing more about Bond or Ian Fleming. We only have Geoffrey Jenkins’ word that Ian Fleming approved of his story and contributed his own ideas to it—without the correspondence between the two men, it is impossible to gauge the exact extent of their collaboration, beyond the fact that Fleming had the outline. It might be that Jenkins destroyed the manuscript of Per Fine Ounce, or kept that and all his other Bond-related material in some place as yet unknown. For the moment, the search has been called off.

John Pearson’s The Life of Ian Fleming was published in 1966. The book ended with Fleming’s death, making no mention of Per Fine Ounce. In his initial letter to Geoffrey Jenkins of 6th June 1965, Pearson had said his deadline for the book was Christmas of that year—as Jenkins did not get the go-ahead for his novel until August 1966 at the earliest, it may be that Pearson decided not to mention the book in case it did not pan out (as, indeed, it did not). In the introduction to the 2003 reprinting of the biography, Pearson wrote that some new information had come to light since 1966, but that on balance he stood by his original assessment.39

By May 1967, Amis had finished writing Colonel Sun.40 The book was published the following year, and James Bond continuation novels have continued in some form since. But one can always wonder about what might have been. Jenkins’ novels are all out of print now, but are easily found in second-hand bookstores and online. Why not try a couple—and then imagine the same author, who knew Fleming and his books well, writing a book about James Bond on a mission in South Africa, having handed in his resignation to M... And who knows? Perhaps, at the bottom of a drawer somewhere, this lost piece of Bond history is gathering dust—Eldorado may yet be waiting to be discovered.

NOTES

1. ‘Master of the adventure yarn passes on’, Daily Dispatch, South Africa, November 15, 2001.

2. http://www.geoffrey-jenkins.co.za

3. Front and back covers of the 1966 Fontana edition.

4. Quoted in the back pages of several Jenkins novels: see, for example, Fontana, 1975, p223.

5. John Pearson begun his first letter to Geoffrey Jenkins (June 6, 1965): ‘Dear Mr Jenkins, I worked with Ian at Kemsley’s some time after you, and so made contact with the same spiritual headmaster, but never with the depth and success you seem to have done…’ In his reply of September 24 1965, Jenkins quoted the part of the TLS review reproduced here.

6-11. Jenkins to Pearson, September 24 1965, Jenkins papers.

12. Pearson to Jenkins, October 1 1965, Jenkins papers.

13. Jenkins to Pearson, October 6 1965, Jenkins papers.

14. Pearson to Jenkins, November 2 1965, Jenkins papers.

15. Letter to Stanley Gorrie (Jenkins’ accountant), March 22, 1966. Jenkins refers to the novel as Per Fine Ounce in this letter.

16. Peter Fleming: A Biography by Duff Hart Davis (Oxford University Press, 1987), pp374-5.

17. A Cleft Of Stars by Jenkins (Fontana, 1975), p20.

18. Sacred Trees by Nathaniel Altman (Sterling, 2000), p170.

19. Letter to Stanley Gorrie, March 22 1966, Jenkins papers.

20. Ibid.

21. Letter to Stanley Gorrie, May 13 1966, Jenkins papers.

22. Ibid.

23. Peter Fleming: A Biography by Duff Hart Davis (Oxford University Press, 1987), pp374-5.

24. Letter from Amis to Victor Gollancz on 1.05.1964, The Letters of Kingsley Amis edited by Zachary Leader (Miramax Books, 2001), p677.

25. It has been rumoured that Amis wrote or rewrote parts of this novel, but his letter to Tom Maschler of Jonathan Cape of 05.10.1964 (Leader, pp685-6) makes it clear he was simply asked to proof-read it.

26. Peter Fleming: A Biography by Duff Hart Davis (Oxford University Press, 1987), pp374-5.

27. Ibid.

28. This and the following passages are all from Per Fine Ounce draft pages, Jenkins papers.

29. This and subsequent quotes from interview with Janson-Smith, 25.02.2005.

30. Jenkins papers.

31. Interviews with Pearson, 25.02.2005 and 28.08.2005.

32. For example, The Bond Files by Anthony Lane and Paul Simpson, (Virgin Books, 2002), p433. One possible reason for the confusion might be that the only two books Fleming wrote that featured Africa were Diamonds are Forever and The Diamond-Smugglers.

33. Precious Stones by Max Bauer (Dover, 1968), p104, and CRC Handbook of Materials Science edited by Charles T Lynch, 1988, p21.

34. A similar job to Percy Sillitoe’s for De Beers, both in real life and in Diamonds are Forever. See Chapter 2, Uncut Gem, for more.

35. The Unripe Gold (Fontana, 1973), p212.

36. The Watering Place of Good Peace (Fontana, 1974), p25.

37. Hunter-Killer (Fontana, 1973), p86.

38. Dana Broccoli interview on Inside Dr No, written and directed by John Cork, 2000.

39. The Life of Ian Fleming by John Pearson (Aurum Press, 2003), p8.

40. Amis to Philip Larkin, May 21 1967, Leader, p712.

Book jacket images: bearalley.blogspot.com, rarebookcellar.com (The Unripe Gold)

Uncut Gem

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

A man runs across a beach, desperate to reach a plane at the far end of it. He hands something to the pilot just as it takes off. The plane rises into a bank of fog, whereupon it erupts into a ball of flame. The man rushes toward the crash, scrambling through the wreckage until his foot hits something. Looking down, he sees a small metal canister. He picks it up and fumbles it open. Diamonds spill into his hand…

If this sounds like the pre-titles sequence of a Bond film, it’s not a coincidence. It is a pre-titles sequence, and it’s from a screenplay based on one of Ian Fleming’s books. For the past 45 years, its existence has remained unknown outside the small group of men who tried to film it.

I first became aware of the story when reading The Letters of Kingsley Amis. I was intrigued by a short letter he had sent fellow writer Theo Richmond in December 1965:

‘I have been having a rather horrible time writing a story outline for one George Willoughby. Based on an original Fleming idea. Willoughby and the script-writer change everything as I come up with it. I gave W. the completed outline five days ago and he has been too shocked and horrified and despairing to say a word since. However, he has already paid me. (Not much.)’¹

I smiled at the familiar writer’s complaint, then stopped in my tracks. What ‘original Fleming idea’? I’d never heard of it, and couldn’t find any reference to it anywhere else. I decided to investigate. My first step was to contact Zachary Leader, Amis’ biographer and the editor of his letters, to ask him if he had any idea where the outline might be. He wasn’t sure, but put me in touch with the Huntington Library in California and the Harry Ransom Center in Texas, both of which hold Amis’ papers. Researchers there sent me inventories of everything they held, and I started trying their patience by asking them to go through boxes that sounded as though they might conceivably contain the outline. After weeks of this, and feeling as though we had examined practically every scrap of paper Amis had saved, I called time. Wherever Amis’ outline was, it didn’t appear to be stored with the rest of his papers.

My attention turned to the other clue mentioned in Amis’ letter: ‘one George Willoughby’. And here I got a little luckier. Willoughby, I discovered, was a Norwegian who had moved to London and become a medium-sized fish in the British film industry. In 1951, he had been an associate producer on Valley Of Eagles, directed and co-written by Terence Young and filmed at Pinewood, the studio owned by The Rank Organisation, at that time Britain’s largest film company. Young went on to direct several of the Bond films, shooting large parts of them at Pinewood.

In 1954, Willoughby had been an associate producer on Hell Below Zero, an adaptation of a Hammond Innes novel made by Warwick Films. Warwick was a company founded by Irving Allen and Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli, and it specialised in making relatively inexpensive but exciting action films. In 1962, Cubby Broccoli would part ways with Allen and form a new company, Eon, with Harry Saltzman. One of the scriptwriters for Hell Below Zero was Richard Maibaum, who Broccoli would take with him: he would go on to have a hand in the scripts to over a dozen Bond films.

Finally, in 1957 George Willoughby had been the associate producer on Action Of The Tiger, another Terence Young-directed film, this one featuring a young Sean Connery. So he had worked with three of the men who would become key players in the Bond franchise: Broccoli, Young and Maibaum. But while this was intriguing, I was no closer to finding the outline of the ‘original Fleming idea’ Amis had written for Willoughby.

But after several months of consulting authors’ societies, literary agents and film libraries, I finally found what I was looking for. To my surprise, a lot of the story had been hiding in plain sight since 1989 in a book called In Camera, a volume of memoirs by Richard Todd.

~

A poster for The Dam Busters (1955)

During the Second World War, Todd had served in the Army’s 6th Airborne Division—he was the first man of the main force to parachute out over Normandy on D-Day. After the war, he had become one of Britain’s biggest film stars. He was nominated for an Oscar for The Hasty Heart in 1949, after which he went on to play several leading roles, including starring opposite Marlene Dietrich in Alfred Hitchcock’s Stage Fright. However, he is probably best remembered today for playing Wing Commander Guy Gibson in the classic war film The Dam Busters.

Like Willoughby, Todd had also worked with many of the people who were to become central to the James Bond series. Although he was a contract player with Rank’s main rivals, the Associated British Picture Corporation (ABPC), who were based at Elstree Studios, he sometimes worked on ‘loan-out’ for Rank, for example on Venetian Bird, an adaptation of a Victor Canning thriller.

He had also made a film for Cubby Broccoli: The Hellions, a quasi-Western shot in South Africa in 1961. The following year, he was one of the star-studded cast of The Longest Day, an adaptation of Cornelius Ryan’s account of D-Day. Todd played Major John Howard, who had been his superior officer on the day in real life. On the set in Caen in France, he met a ‘rather shy’ young Scottish actor with a small part in the film: Sean Connery.²

Richard Todd with Eva Bartok in the 1952 film Venetian Bird, also known as The Assassin, an adaptation of a Victor Canning thriller

In April 1962, while Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman were busy finalising their contract with United Artists for the first Bond film, Dr No³, Todd was informed that his contract with ABPC would not be renewed the following year. This was a body blow: it meant that he would now have to fend for himself in the jungle of Britain’s rapidly declining film industry, which was under increasing pressure from Hollywood. But he had at least one iron in the fire, in the form of his friend George Willoughby, who ‘had secured an option on the screen rights of an Ian Fleming book, The Diamond Story [sic], an intriguing exposé of illicit diamond-buying in Africa and of the undercover activities of agents who worked to counteract it’.⁴

So here it was: this was the elusive project Amis had been working on. The Diamond Smugglers was Fleming’s first foray into full-length non-fiction, and apart from the guidebook Thrilling Cities remains the only one of his books not to have been filmed. It was originally published in 1957, collecting a series of articles in The Sunday Times in which Fleming had explored the shady world of diamond trafficking. A new edition of the book was published in 2009, with an introduction by Fergus Fleming, the writer’s nephew. ‘The success of Bond tends to eclipse Ian Fleming’s other talents,’ he tells me. ‘It’s often forgotten that he was also an accomplished journalist, travel writer and children’s author.’⁵

Ian Fleming had become fascinated by the illegal trade in gemstones in 1954, when he had discovered that the world’s biggest diamond-seller, De Beers, had set up its own private intelligence agency, the International Diamond Security Organisation, to try to combat it. IDSO was run by Sir Percy Sillitoe, who had previously been the head of MI5. Fleming met with Sillitoe and other diamond industry insiders, and used much of what he learned as background material for Diamonds Are Forever, largely set in the United States.⁶ The title of the novel was drawn from De Beers’ slogan.

Three years later, Fleming was drawn back into the world of diamonds. IDSO had blocked several plots by international criminal networks to bring diamonds illegally out of the mines of South Africa, Sierra Leone and elsewhere, and had been disbanded. Sillitoe, irritated that he and the organization had not been given more credit for their successes, decided to publish a book about it. His intention was for it to be a sequel to his 1955 memoir Cloak Without Dagger, and with that in mind he commissioned one of IDSO’s senior agents, John Collard, to ghost-write an account.

Collard was an old hand in the espionage game. He had been in MI5 in the early part of the Second World War, but had then moved to the counter-intelligence agency MI11, becoming its head by 1946. He then rejoined MI5 and played a major role in the capture and conviction of the ‘atomic spy’ Klaus Fuchs, before heading off to South Africa to join IDSO.⁷

Collard revisited his and other agents’ reports and wrote the book. Sillitoe sent the manuscript to Denis Hamilton at The Sunday Times for his view; Hamilton liked it, but Leonard Russell on the paper felt that a professional journalist would be able to spice it up. They suggested that Ian Fleming, who worked for the paper, interview Collard with the aim of producing a series of articles. All involved agreed, and so in early April 1957 Fleming took an Air France Caravelle to Tangiers to meet John Collard. The two men quickly established a rapport, and Fleming started work.⁸

This mainly consisted of editing and redrafting the original manuscript. Collard had detailed the organisation’s frustrations, failures and successes in clear, lively prose, and it probably would have sold well had it been published as it was. But it was no thriller. Fleming went through the text, cutting anything he felt was dull or overly complicated and heightening the most exciting passages as only he knew how. He also adapted information from Collard’s source material: one IDSO agent’s report in Collard’s papers has ‘Passage omitted I.F.’ and ‘Name omitted I.F.’ all over it in Fleming’s distinctive scrawl.⁹

The biggest change Fleming made was not to the content, but to the perspective. Collard had written the book as though Sillitoe were the narrator. Fleming kept most of Collard’s material, but rewrote it so that he, Ian Fleming, became the narrator, the intrepid investigative journalist flying out to Tangiers to interview the mysterious hero of the tale, who he made Collard instead of Sillitoe.

This switch was clever in several ways. Firstly, Sillitoe was at that point nearly 70 years old, and was not nearly as compelling a subject as Collard, who was in his mid-forties and therefore a man with whom readers could more readily identify. Sillitoe was largely a desk man, while Collard had seen extensive action in the field, both with MI5 and with IDSO—indeed, he wrote of his own actions in the third person throughout his manuscript. Sillitoe was the M figure of the organisation, and Fleming must have realized that the public would be drawn to someone more like Bond.

This shift of focus from Sillitoe to Collard allowed Fleming to create something more reminiscent of his own famous thrillers, as well as to add some local colour and texture. The framing device of the interview allowed Fleming to break up Collard’s long passages of close exposition about the diamond industry with some of his own brand of intrigue, bringing in references to life in Tangier, other spies such as Richard Sorge and Christine Granville and, of course, James Bond.

Either prompted by others or on his own initiative, Fleming also gave several of the people featured in the book different names, including Collard. The book discussed at length how IDSO had foiled several unscrupulous gangs, so there might have been some concern about blowback following publication. For Collard, Fleming chose the rather Bond-ish ‘John Blaize’—in the germ of a scene in one of his notebooks, he had had Miss Moneypenny suggest ‘Major Patrick Blaize’ as a cover name for Bond.¹⁰

Fleming portrayed Collard/Blaize as a quieter, shyer character than Bond, although readers would learn that he owned 24 fine white silk shirts and intended to spend 48 hours gambling intensively in Monte Carlo ‘to wash the last three years and the African continent out of his system’.¹¹

In 1965, Leonard Russell wrote to Collard to ask him about his recollections of Fleming for a biography he was writing of him with John Pearson—Pearson eventually took over the job completely—and Collard gave a detailed account of how the book had come about and how he had met Fleming. In much the same way he’d ghost-written himself into Sillitoe’s memoir, he also wrote this up in the third person. He reveals the week included them playing golf together and attending parties, and that they kept in touch in subsequent years:

‘In the bar at the Royal St Georges or Rye Golf Club, they could sometimes be seen having a private yarn.’¹²

The two men evidently got on well in Tangiers, but Fleming’s presentation of their meetings in the book is largely fiction. No doubt he asked Collard for clarification on some points, but his work was largely editorial: he took passages from Collard’s book, rearranged and simplified them, and then had ‘Blaize’ speak them aloud while he, Fleming, supposedly leaned in and listened, interjecting occasional questions. In this way, the book took on the tone of a fascinating secret story being told in a darkened corner of a bar in the tropics, automatically giving it more vigour. Fleming could probably have done most of this work in London—but then, that wouldn’t have been as exciting, or got him a few days’ golf and partying in Tangiers.

~

To pre-empt any legal difficulties, Fleming sent proofs of his version of the book to The Diamond Corporation, De Beers’ distribution arm in London. The move didn’t work. Although the company initially appeared pleased with the text, it later took exception to several elements, and Fleming was forced into rewrites.¹³ But finally, in September 1957, the articles began to be serialised in The Sunday Times. Readers learned about ‘Monsieur Diamant’, a ‘big, hard chunk of a man with about ten million pounds in the bank’. Outwardly a respectable entrepreneur, his diamond-fencing activities had made him ‘the biggest crook in Europe, if not in the world’. Another episode concerned a bravado attempt to fly 1,400 stolen diamonds out of Chamaais Beach in South-West Africa, which failed when the plane crashed on take-off.

The articles were collected to form a book, titled The Diamond Smugglers, which was published in November with an introduction by Collard (under the Blaize pseudonym). The book didn’t differ a great deal from the manuscript Collard had originally written, but it had been souped up, texture had been added and, above all, Fleming’s name had been appended to it. As a result, it received a level of marketing almost equal to that afforded to the Bond novels at the time.¹⁴

Fleming was happy with his scoop, but not entirely satisfied with the way the project had turned out. On the fly-leaf of his own copy of the book, now stored at Indiana University’s Lilly Library, he noted:

‘This was written in 2 weeks in Tangiers, April 1957. The name of the IDSO spy is John Collard. Sir Percy Sillitoe sold the story to the Sunday Times & I had to write it from Collard’s M.S. It was a good story until all the possible libel was cut out. There was nearly an injunction against me & the Sunday Times by De Beers to prevent publication of the S. T. serial. Rightly, they didn’t like their secrets being sold by an employee. Lord Kemsley & Collard shared the profits of this—a third each, which was a pity as I sold the film rights to Rank for £12,500. It is adequate journalism but a poor book & necessarily rather “contrived” though the facts are true.’¹⁵

Perhaps as a result of his irritation at the suppression of some of the story’s more exciting aspects, Fleming’s view was overly pessimistic. The fact that Rank was prepared to pay a sizeable amount for the rights to a compilation of newspaper articles he had written in a fortnight was a sign of the growing interest in his work from the film industry. In 1954, Gregory Ratoff had taken a six-month option on his first novel, Casino Royale, for $600, and shortly after that CBS had bought the television rights to the same book for $1,000. The following year, Rank had snapped up the rights to Moonraker for £5,000. Casino Royale was rapidly made into an hour-long TV adaptation, with Barry Nelson as James ‘Jimmy’ Bond and Peter Lorre as Le Chiffre. Rank’s Moonraker film never got off the ground.¹⁶

Rank was, initially at least, keen to publicise the fact that it had bought the rights to the book. The Bookseller noted that it had bought the rights for ‘an unusually high figure’, and had ‘commissioned Ian Fleming to prepare the film treatment’¹⁷, and ‘The Diamond Smugglers Story’ was included in Rank’s programme for 1958 along with The Thirty-Nine Steps and Lawrence of Arabia (both of those were prematurely announced, being released in 1959 and 1962 respectively). But 1958 passed, and the film didn’t materialize.

~

Poster for Chase a Crooked Shadow (1958)

That’s the traditional story of The Diamond Smugglers, mentioned in passing in dozens of books and articles. A slightly obscure Fleming work, not featuring James Bond. A success, but not one of his greater ones. The film rights sold, but no film made. Case closed.

Well, not quite. There were attempts to film The Diamond Smugglers, serious and prolonged attempts, as Todd’s memoir showed. I contacted the actor’s agent, but was told that due to frailty and a hazy memory he didn’t feel he could add to what he had already written. This was understandable: Todd was approaching ninety and, unknown to me, suffering from cancer. I had by now also contacted John Collard’s family, who kindly provided me with a great deal of material, including both his relevant correspondence from the time and the original manuscript of his book. Adding this to the information in Todd’s memoirs and other sources, I started to piece together the rest of the story.

Willoughby set up his own production company in 1959, and at some point between then and 1962 obtained the film rights to The Diamond Smugglers. In a letter to a former colleague in 1965, John Collard wrote that he had met Willoughby ‘about five years ago at the request of Ian Fleming’.¹⁸

From subsequent events, it seems that Rank may have told Willoughby that they had given up on trying to adapt the book, but that if he could put together the elements of a commercially viable film, they would distribute it. They later did just that with another Willoughby production, Age of Innocence, which had featured Lois Maxwell and Honor Blackman.

Todd and Willoughby became partners in 1962, and set to work: Derry Quinn, who had worked as a story supervisor on Chase A Crooked Shadow, a thriller Todd had made in 1958, was hired to write a treatment. As well as Todd’s contacts within the industry and star power—presumably the original intention was for him to play Blaize—the actor also knew South Africa. While making The Hellions, he had been struck by the potential for a film industry there: it had widely varying scenery and climate, a lot of investors looking for overseas outlets, and a large pool of English-speaking actors.¹⁹

As The Diamond Smugglers took place in that part of the world, Todd now returned to his South African contacts, inviting to London Ernesto Bisogno, a businessman he had met on his Hellions trip who had dabbled in small-scale film production and was now forming a production company in Johannesburg. Bisogno was accompanied by an official of the South African Industrial Development Corporation, who Todd had also met the previous year. Their reactions to the project were apparently very favourable, and Todd was optimistic that he would be able to persuade ABPC to distribute the film once it was made. However, work on the screenplay was slow, with Todd’s flat becoming ‘a charnel-house of abandoned drafts and screen treatments’.²⁰ Fleming’s book was essentially a series of unconnected episodes: crafting an exciting, coherent and commercial script from them would prove no easy task.

In April 1963, a full year after starting work on the project, the two men had a breakthrough: John Davis, the head of Rank, put them in touch with Earl St John, who was in charge of productions at Pinewood. St John had been an executive producer on Passionate Summer, a film Willoughby had produced in 1958. He liked their pitch, and as a result Rank funded a trip to South Africa and South-West Africa (now Namibia) in May 1964 to scout locations in which to set the screenplay for The Diamond Smugglers.²¹

~

Season of Doubt, a 1968 spy thriller by Jon Cleary set in Beirut

By now a new writer had arrived on the scene: the Australian Jon Cleary, then best known for his novel The Sundowners, the film of which had starred Robert Mitchum and Deborah Kerr and had been nominated for five Academy Awards. Now in his nineties, he still vividly recalls his work on The Diamond Smugglers. ‘My doctor says my body is ninety but my head’s fifty,’ he laughs when I speak to him on the phone from his home in Sydney. According to Cleary, Rank had originally bought the rights to the book because of Fleming’s name. ‘They disowned it when they realised it was a grab-bag of pieces he had written one wet weekend. There was no story. So they put it on the shelf.’²²

But now The Diamond Smugglers had another shot. It was not only back on Rank’s radar—they were putting up money to develop it. Accompanying Todd, Willoughby and Cleary on the trip to Africa was the American director Bob Parrish, who, according to Cleary, had agreed to direct the film subject to a satisfactory script being developed. Cleary and Parrish both lived in London and knew each other; Cleary says Parrish put him forward for the project. Parrish, who had won an Oscar as an editor, had directed an adaptation of Geoffrey Household’s A Rough Shoot, from a script by Eric Ambler, and Fire Down Below, co-produced by Cubby Broccoli.

‘We landed in Johannesburg on a Sunday afternoon,’ Cleary remembered. ‘There were three thousand people there to meet us at the airport! We stayed in the Langham Hotel, which was the place to be. Everything was laid on for us, and all kinds of avenues of research were opened—I knew nothing about diamonds. One day, a European woman—Contessa something-or-other—turned up at my hotel room to discuss the business, and emptied her chamois bag, spilling diamonds onto the table. It was about three or four million Rand, just sitting there!’

After spending a few days in South Africa, where they scouted locations in Johannesburg, M’Tuba’Tuba and Pretoria, the group flew to South-West Africa’s capital, Windhoek. They were shown around by Jack Levinson and his wife Olga, who lived in a castle-like residence that had been built for the Commander-in-Chief when the country had been a German colony. The Levinsons were ideal guides for their mission: as well as being the city’s mayor, Jack was also a lithium entrepreneur who had discovered diamonds on the Skeleton Coast, while Olga had recently published a history of the country.²³

By now, the Bond films were big business, and with the release of Goldfinger in September, about to become a global phenomenon. Was the intention to leverage Fleming’s material into a Bond-style plot? Not according to Cleary: ‘It was always going to be much more realistic than the Bond films. We wanted to make use of the fact that we had these remote, exotic locations, but craft something much more down-to-earth, that nobody had seen before.’

Cleary, like Derry Quinn before him, was desperately looking for a way to connect the disparate elements of Fleming’s book into an exciting plot. In South-West Africa, he finally hit upon an idea. ‘Bob liked it. We told Richard—it would involve him being the villain, for a change. He jumped at it. The idea was for Steve McQueen to play the lead. I’ve forgotten who they wanted for the girl, but it was one of the top stars.’

McQueen, who had become well known after The Magnificent Seven in 1960, had just made The Great Escape, which had catapulted him to greater fame. Whether or not he would have been interested or available for The Diamond Smugglers is another question, but it’s fascinating to think of him in a Fleming adaptation.

Cleary’s original idea for the script was based on a story he had heard while the team were scouting the Skeleton Coast, about a man who sets up a model aeroplane club in the De Beers’-protected town Oranjemund, and then uses the model planes to try to smuggle some diamonds out. Fired up with the potential of this idea, Cleary ‘went away and wrote a screenplay’. I ask him to repeat this to be certain I’ve heard correctly. There are no references to a completed screenplay in Todd’s memoirs—or anywhere else. A script of an unfilmed Ian Fleming book, written in the Sixties by a well-known novelist, with funding by Rank… well, that would be something. ‘Did you keep a copy?’ I ask quietly. Cleary chuckles. ‘I’m afraid I’ve never been a hoarder,’ he says, and my heart sinks. He tells me that the State Library of New South Wales has his papers, but that they often call, begging him to send them his latest manuscript ‘before I throw it out’.

This doesn’t sound hopeful, but I contact the library anyway. And they have it. After obtaining permission from Cleary and his literary agency, I am sent a copy. I crack it open, and stare at the title page with amazement. ‘The Diamond Smugglers by Ian Fleming. Draft screenplay by John Cleary.’ I had gone looking for Amis’ story outline, and had instead found a completed screenplay.

~

The script is dated October 28 1964, and is 149 pages long. It begins:

‘EXT. BEACH. SOUTH WEST AFRICA. EARLY MORNING.

We open on a LONG SHOT of a desert, grey-blue and cold looking in the dawn light…’²⁴

The protagonist has been renamed: instead of John Blaize, he is now Roy O’Brien, a tall, quiet American secret agent who is sent to a diamond mine in Johannesburg under cover as a pilot. His mission: to infiltrate and break up a ring of smugglers preparing to make a huge deal with the Red Chinese. O’Brien reads very much as though written with McQueen in mind. We are told he is ‘marked with the sun and the scars of a man who has spent a good deal of his life in the outdoors’ and that ‘he was a boy once quick to smiles’ but is now ‘a man who has seen too much of sights that did not provoke laughter’. He is quick-witted, laconic, but very likeable.

We first meet him in Amsterdam, where he is staking out Vicki Linden, a beautiful young South-West-African diamond-smuggler of German descent. She is reminiscent of the character Tiffany Case in Fleming’s novel Diamonds Are Forever, but somewhat softer and more naive (without being irritating). He follows Vicki to South Africa, and she tells him her ambition is to have a diamond ‘for every day in the week’. He asks how far she has got in this and she wrinkles her nose and replies ‘Only Monday’, to which he retorts: ‘Give me the chance and I’ll try and dig up Tuesday for you.’

Despite the change from Blaize to O’Brien and the addition of new characters, Cleary’s screenplay is remarkably faithful to the tone of Fleming’s book, and takes a lot of cues from it. Cleary used locations, incidents, technical information and a lot of other elements and ideas from the book, and wove a thriller plot around them. The opening sequence is clearly inspired by the failed attempt to fly diamonds out from Chamaais Beach, although this time the plane doesn’t simply crash but explodes mid-air. China’s increasing interest in the illegal diamond trade, discussed at several points in the book, becomes the political backdrop of the plot; the description of security measures employed by mining companies is dramatised in a scene in which O’Brien is X-rayed; like Collard/Blaize, he makes use of a safe house in Johannesburg’s back streets; and so on.

It is a very different beast to the Bond films. There are no nuclear warheads or hidden lairs: it is, as Cleary says was the intention, a gritty, down-to-earth thriller. Nevertheless, there are some suitably baroque and Fleming-esque touches. One of the villains is a diamond-smuggler called Cuza, who weighs over four hundred pounds ‘but walks with a delicate step’ and likes eating chocolates: ‘Stone-bald, he wears dark glasses; a balloon head rests on a balloon body; he could be a clown or a killer.’

Cuza and his black sidekick Daniel work out of a windswept drive-in cinema projectionist’s office. In one memorable scene, Daniel stalks O’Brien with a sniper rifle from his position on a catwalk running along the top of the cinema screen.

Cuza is in competition with a villain in a similar mould to Fleming’s: Steven Halas is a wealthy German South-West-African businessman who likes giving lavish parties (at which he serves Bollinger ’55) and taking photographs of big game, but beneath the veneer of sophistication he is greed personified. However, the real villain of the piece is revealed in the final act to be Ian Cameron, a womanising Scot who is the mine’s field manager, and who is gently reminiscent of both Bond and Fleming. This, presumably, is the role that had been earmarked for Todd.

As well as drawing incidents and ideas from Fleming’s book, the script is faithful to its tone, especially in its evocation of the sticky climate of fear and temptation permeating a diamond mining community. The shabbiness of O’Brien’s accommodation provokes the script’s one direct reference to Fleming’s best-known creation, when his colleague Spaak is amused at its unsuitability and asks what has become of spies who only operate in five-star hotels. ‘You need a nice low number,’ O’Brien replies, ‘Like 007. Whoever heard of a spy called 42663-stroke-12568?’ ‘What’s that?’ asks Spaak. ‘My social security number,’ comes the dry reply.

Highlights include two brutal hand-to-hand fights, one of which ends with the death of the monstrous Cuza, and a climactic car chase, which happens during an elephant stampede.

All told, the script is a cracker: a taut thriller with believable characters, snappy dialogue and a compelling plot. Its strongest features are its evocation of the Skeleton Coast—you can almost feel the dust and the dirt of this place that ‘breeds seals, jackals and madmen’, as one character describes it—and the subtle shading of the relationship between O’Brien and Vicki. Cleary also added some extra spice to the traditional police/spy story with elements of the Western and film noir, in a manner occasionally reminiscent of Orson Welles’ A Touch Of Evil. His script is free of the troublesome plot holes, inconsistent characterisation and mixed tones common in many films of the time.

According to Todd’s memoirs, in the summer of 1965 Rank signed an option to buy and produce the film, while on 14 June of that year, Willoughby wrote to John Collard to tell him that the production looked like it was back on the table:

‘You may recollect that we met a few years ago in connection with the proposed production of a film based on Ian Fleming’s “The Diamond Smugglers”. Due to various circumstances at the time, these plans did not materialise. It is now a possibility that I shall be able to set up a production on this subject.’²⁵

The letter is headed ‘Willoughby Film Productions Limited’ with an address in Sackville Street in London—but next to it Willoughby typed another address for Collard to reply to: Pinewood Studios, Iver Heath, Bucks.

Willoughby was contacting Collard again because he wanted his permission to use the character of John Blaize (the name O’Brien seemingly having been dropped). As a sweetener, he offered Collard a role as a technical adviser to the production.

Collard replied that De Beers should be consulted about the latest plans for the film, and asked for more details about it: would it be a documentary sticking closely to the book, or partly fictional?²⁶ On 21 June, Willoughby wrote to Collard again, writing that the film he had in mind was a ‘feature entertainment’, which would necessitate departing from Fleming’s book, as that had mainly consisted of ‘a number of incidents without a dramatic story line or link’. He understood that Collard might feel they were straying too far from the facts, but gave a surprising precedent for it:

‘Fleming himself wrote for the Rank Organisation, a film treatment on this subject and although he used the name of John Blaize for the hero, his treatment had, nevertheless, very little to do with the actual articles he wrote for the “Sunday Times”.’²⁷

This is the first mention of the existence of a film treatment for The Diamond Smugglers by Ian Fleming since The Bookseller’s report of its commissioning in 1957—but it would not be the last. On 1 September 1965, Collard received a letter from B.J. Rudd, an old acquaintance, who had enclosed a small cutting from The Sun from 25 August, titled ‘Fleming film’:

‘An 18-page outline for a film about illicit diamond-buying written by Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, is to be turned into a £1,200,000 film.’²⁸

Collard and Willoughby, meanwhile, continued to correspond, with the producer revealing two new pieces of information in a letter on 27 August: a script was being completed by yet another writer, Anthony Dawson (‘who lives not far from you in Sussex’) and that the protagonist’s surname had now been changed from Blaize to Blaine, to avoid confusion with Modesty Blaise.²⁹

For anyone familiar with the James Bond films, the reference to Anthony Dawson is almost surreal: could this be the British character actor who had played Professor Dent in Dr No and who had been the presence (although not the voice) of arch-villain Ernst Stavro Blofeld in both From Russia With Love and Thunderball? It would seem so. Terence Young, who directed all three of those Bond entries, cast Dawson in several of his films, including Valley of Eagles and Action of the Tiger, both of which had had as associate producer one George Willoughby. It seems implausible that there were two Anthony Dawsons who worked on Ian Fleming projects in the Sixties, and that Willoughby collaborated with both. Dawson’s son confirms that his father lived in Sussex during this period, and wrote several film scripts.³⁰ Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to locate any material relating to The Diamond Smugglers.

A few weeks later, Barbara Bladen, a critic at the San Mateo Times in California, reported breathlessly on the film in her column:

‘We’ll have to start getting used to someone else playing James Bond in the Ian Fleming stories! Sean Connery has gone back to being Sean Connery and the Fleming pictures roll on. Latest before the cameras is “The Diamond Spy” on location in South Africa, Amsterdam and the Baltic coast of Germany. Richard Todd will play the slick agent. The author first wrote the book as a series of newspaper articles in 1957 and came out in book form as “The Diamond Smugglers.”’³¹

The changing of the protagonist from a newly coined character to the world-famous James Bond is probably either Willoughby or Bladen’s hyperbole—perhaps even a way around the fact that they had not yet resolved what to call the character. The locations listed are intriguing: South Africa and Amsterdam were both featured in Cleary’s 1964 screenplay, but the Baltic coast of Germany was not. Could there have been another script by this time—or did Willoughby merely have an idea for one?

The title The Diamond Spy, which now started appearing in the press, did not please John Collard. On 3 January 1966, he wrote to Willoughby at Pinewood:

‘If the revised title is seriously proposed, I am afraid that as far as I am concerned the film will start off on the wrong foot, whether it is described as fictional or coincidental, and the object of this letter is to advise you in the friendliest possible manner to bear in mind my personal interest and the need to consider the risk of libel.’³²

In a more placatory hand-written postscript, Collard explained that Fleming had originally planned on calling his book The Diamond Spy, but had changed it at Collard’s request: ‘The description “spy” carries with it a derogatory meaning,’ he explained to Willoughby, ‘and quite apart from its inappropriate use to describe “Blaize”, I myself take strong exception to it.’ The word ‘spy’ was often used in books and films at the time, and Fleming had of course used it in one of his titles, but Collard had worked for MI5, and in that and other intelligence agencies, the word was usually used to refer to informants and traitors.

Collard’s letter seems to have been the first between the two men since August 1965, but it begun another flurry of correspondence. Willoughby immediately tried to reassure Collard that The Diamond Spy was merely a working title, which they were using ‘because this is the title Fleming used for his story-line’. He invited him to lunch the next time he was in London to tell him more about the film.³³

By now, Willoughby had hired Kingsley Amis as a ‘special story and script consultant’. This news was reported in the American film industry magazine Boxoffice in January 1966:

‘Kingsley Amis, novelist, critic and authority on the work of Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond, has been engaged as special story and script consultant on the new £11/4 film of Fleming’s “The Diamond Spy”, it was announced last week by British producer George Willoughby. The film, to be made early next year by Willoughby, in association with Richard Todd’s independent company, is based on a story outline written by Ian Fleming but never completed by him. This outline was drafted by Fleming following his own investigations into international diamond smuggling, which he wrote up as a series of articles for a Sunday newspaper in 1957. Later, these articles were collected and published in book form under the title of “The Diamond Smugglers”.

Now Amis, author of the recently published “James Bond Dossier”, has been called in as a Fleming expert to develop the story, characters, situations and incidents so as to give “The Diamond Spy” film an authentic Fleming flavor. When he has completed this task, W. H. Canaway, who wrote the script of “The Ipcress File”, will take over all the material, from which he will write the final screenplay.’³⁴