The name is Gunn. James Gunn.

This is a follow-up to Looking for James Gunn.

Part I. A Spy In Jamaica

In February, producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson announced that they were stepping down and handing creative control of the James Bond films to Amazon. Since then, there has been a lot of speculation about how Amazon might proceed: according to The Hollywood Reporter, before the deal was struck the company had pitched ideas for several TV series: one centred around Miss Moneypenny, another on Felix Leiter, ‘and maybe even something involving a female 007’. Broccoli and Wilson were apparently not impressed, but all these ideas and more now seem much more likely.

It wouldn’t be the first time Bond has come to the small screen. In October 1954, CBS broadcast a live TV adaptation of Ian Fleming’s first novel, Casino Royale, starring Barry Nelson as American agent ‘Jimmy Bond’. The novel was most recently adapted into Daniel Craig’s first Bond film in 2006, so it seems unlikely Amazon will revisit that particular work any time soon. However, they might be interested in another TV project from the 1950s, with a script written by Ian Fleming himself. Let’s talk about Gunn. James Gunn.

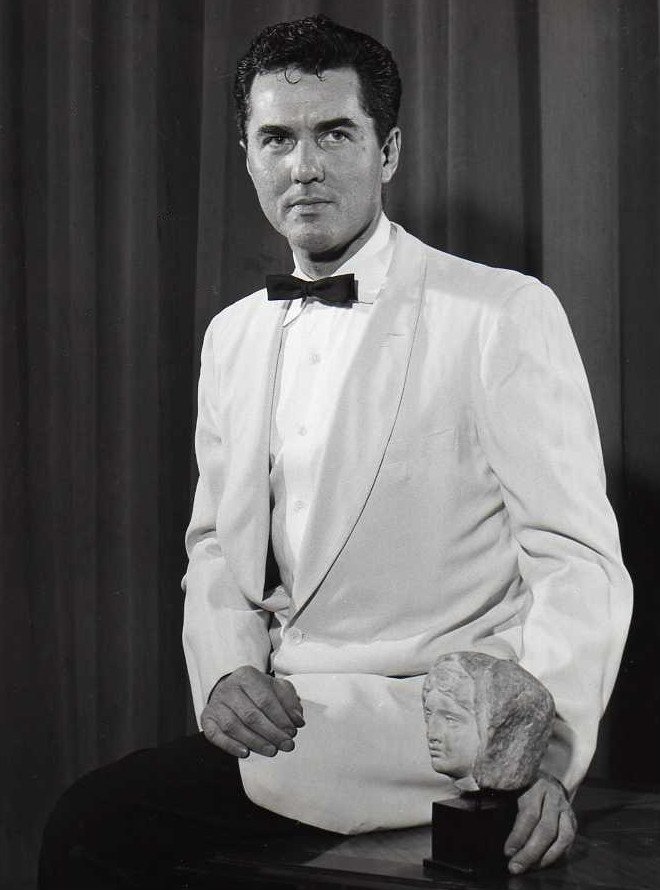

Douglass Watson in the play Season of Choice, 1959. [Image: Wikipedia.]

Starting in late 1955, American TV producer Henry Morgenthau III had been trying to get a new project off the ground: a TV series about an American secret agent working in Jamaica. Working with another producer, Martin Stone, by April 1956 he had an eight-page proposal for the show:

‘Captain Jamaica of the CIC is conceived as a film television show of high adventure directed principally toward an audience of young people, but intended to contain sufficient solid conflict and credibility to be interesting also to adults […] It should attract an audience similar to that of the Lone Ranger, Robin Hood or Lassie.’[i]

The idea was to film on location in Jamaica, and two writers were earmarked to write the pilot, Halsey Melone and Henry Misrock. George Justin, who had been production manager for On The Waterfront, was envisioned as performing the same role for this, and Morgenthau intended to ask Sidney Lumet to direct the pilot. Lumet was an experienced TV director who had worked with Justin on several projects: a year later he would direct 12 Angry Men (with Justin as an associate producer).

Morgenthau wanted Broadway actor Douglass Watson to play the series’ protagonist, ‘a modern Scarlet Pimpernel in the service of the United States Army Counter Intelligence’. A legendary pilot during the Second World War, towards the end of the war his plane exploded and crashed into the sea while operating near Jamaica. Although reported dead, no traces of his body were found and a legend built up that he had survived, which some put down to ‘native superstition’.

But he is alive, and still on active service with the US Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), as well as working for the CIA, the State Department and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics when occasion demands. Assisted by a Jamaican boy, ‘Ackey’ Montego, he lives on a cabin cruiser called The Silver Seas, posing as an eccentric searching for buried pirate treasure. The boat is also his headquarters: below deck, he has a communications centre with radar, transmitters and scrambling and coding equipment with which he communicates with his superiors, as well as a range of disguises he assumes when venturing onto shore. He is very much in the heroic mould:

‘Captain Jamaica’s unique success as a secret agent stems from his phenomenal accomplishments. He can pilot or navigate a ship or plane, and operate all kinds of communications equipment. An ex-West Point football star, he has great physical prowess. He can swim underwater like a frogman, and in a tight spot he is expert with a pistol or in the art of judo.

He is equally adept in all the many skills of the professional spy: a master of disguises; fluent in several languages; generally keen to observe and quick to analyse any dangerous situation.’[ii]

This description doesn’t sound a million miles from James Bond, but Morgenthau and his associates don’t seem to have had any knowledge of Ian Fleming or his character when starting their project. The second Bond novel, Live and Let Die, had been published in 1954 and was set in Jamaica, and Fleming wrote all his books at Goldeneye, his home on the island, but Bond was not yet a phenomenon. Morgenthau looks to have been inspired instead by shows like Secret File, U.S.A. This syndicated espionage series starred Robert Alda as intrepid American agent Colonel William Morgan, and claimed to relate true stories of missions behind enemy lines both during and after the war, drawn from U.S. intelligence files. One of the writers intended for ‘Captain Jamaica’, Henry Misrock, had written an episode of Secret File, U.S.A., and Morgenthau’s proposal for his show claimed that the U.S. Army had promised to provide his project with non-classified information on CIC activities, a consultant, special military equipment, and footage of personnel and equipment. ‘In return we have assured the Army that its personnel and activities will be presented in a favorable light.’[iii]

Nevertheless, a project revolving around a secret agent in Jamaica seems almost tailor-made for Ian Fleming’s involvement. The connection came through Lady Jeanne Campbell, the grand-daughter of the Canadian press magnate Lord Beaverbrook, who knew both Morgenthau and Fleming. On 16 July 1956, Morgenthau wrote to Fleming at Kemsley House in London:

‘Dear Mr Fleming,

As you requested in your cable to our mutual friend, Jean Campbell, I am forwarding you information concerning our plans for making a series of television films on the island of Jamaica.’[iv]

Morgenthau wrote that Campbell had told him Fleming spent a considerable amount of time in Jamaica and that, having read his James Bond stories and some brief biographical accounts, he felt confident Fleming could provide the project ‘with exactly the kind of stories that we are looking for’.[v] He summarised the technical and commercial side of the project and attached a memorandum on the latest concept for the series, which was now titled ‘Commander Jamaica’. He ended by saying that that they could perhaps meet and discuss further when Fleming was next in New York, which he understood would be on 31 July.

The ‘Commander Jamaica’ proposal is broadly similar to the previous incarnation, but the protagonist is now described as ‘a modern Scarlet Pimpernel in a branch of the British or United States intelligence (to be specified). We had originally conceived of him as a CIA agent, but there were many obvious advantages connected with this particular series in presenting him as a member of the British Secret Service.’[vi]

The memorandum is undated in the files, but it seems plausible that both the change in title and possibly in nationality were as a result of Morgenthau being alerted to Ian Fleming – James Bond is of course a British agent, but his rank of Commander had also been mentioned in Moonraker, which had been published a year earlier.

Fleming replied to Morgenthau three days later with his ‘immediate thoughts’ on the project.[vii] He started by saying he is enthusiastic about it, before giving advice on other possible filming locations they might not have considered, including ‘the Blue Mountains, oil drilling , an excellent desert, Arawak middens and ruins and, though these are limited, real architectural beauties such as can be found in Spanish Town.’[viii]. ‘Oil drilling’ in this list is handwritten by Fleming, crossing out his typed suggestion of ‘the bauxite mines’. Bauxite mining had been mentioned in Morgenthau’s background material on Jamaica, so perhaps Fleming realised it wasn’t a further suggestion – but he would come back to this. Fleming added that there are also ‘fairly harmless sharks’ on the island that could be ‘captured alive without difficulty’, and gave several other detailed suggestions on the practicalities of production in Jamaica.

Regarding the series’ storyline, he noted – as one might perhaps expect Ian Fleming to do – that there doesn’t seem to be any ‘feminine interest’. He observed that there are ‘plenty of beautiful girls’ in Jamaica who might be interested in taking small parts ‘getting captured, rescued, tortured and the like’. He also felt the series might need a ‘basic villain with a band of minions’ and suggested a new title for the series: ‘Commander X’. The initial, he explained, is derived from Xaymaca, the original name for the island. It’s a more evocative title than ‘Commander Jamaica’, but Fleming noted it might have ‘snags’, presumably because the production would be relying on close cooperation with Jamaican authorities and it would not be nearly as appealing to them.

He ends the letter saying he is flattered to be considered but playing a little hard to get, noting that the thrillers he writes in Jamaica for two months every year make him ‘a considerable amount of money’ and that if he were to spend that time writing for a TV project it would knock out his book for that year. Writing in England would be out of the question as he works for the Sunday Times while there and doesn’t have the time, and taking a year’s sabbatical from his job would be an ‘expensive sacrifice’. He also mentions that Rank is trying to persuade him to write for them but he is reluctant to acquiesce, though he is more disposed to Morgenthau’s project due to the ‘excellence of the idea, my affection for Jamaica and my reading into your letter and memorandum the feeling that this is a useful and stimulating venture considerably removed from the usual film machine’. Finally, he says he looks forward to meeting Morgenthau in New York.

It’s an elegant and cleverly phrased letter. He comes across as an authoritative, practical, and useful person to have on board, with plenty of local contacts and knowledge to draw on. But he’s also a big catch and is indicating that he won’t come cheap.

The strategy seems to have worked. On 27 August 1956, Fleming wrote to Morgenthau again, thanking him for ‘a most splendid last night in America’ and adding that he has airmailed ‘a 9-page outline of the whole series and a 28-page script for the Pilot’ for ‘James Gunn – Secret Agent’.[ix]

This is where this story usually ends. The biographies of Ian Fleming by John Pearson, Andrew Lycett, and most recently Nicholas Shakespeare all discuss this project briefly, and all say much the same thing. Fleming sent Morgenthau material featuring a villain named Dr No and missiles veering off course, but the TV project soon foundered. Fleming then decided to re-use both the villain and some of the plot for his sixth novel, titled Dr No, which was published in 1958. A few tantalising details pepper the biographies and other sources, but the material has never been published and remains one of those Fleming projects that seem certain to stay a footnote and never see the light of day.

But the material has in fact survived, and has been sitting under our noses all this time. Although it is not at all easy to find online (even when looking for it), Fleming’s outline and script for ‘James Gunn – Secret Agent’ are both housed in the stacks of the Lilly Library in Bloomington, Indiana, which also has the manuscripts of several Bond novels. The ‘James Gunn – Secret Agent’ outline has call number PN6120.S42 J27, and the pilot script is PN6120.S42 J271. Both these folders of unpublished Ian Fleming material are viewable by the public, either by visiting the library in person or ordering digitised scans for a fee. I did the latter.