The Lives of Carruthers

Read the previous chapters:

IV. Saving England

‘I could appreciate the need in a strange place of some point of support, of one or two things scattered around which are familiar and understandable even if they are only Sydney Horler’s novels, a gin and tonic.’

– Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (1936)

Sydney Horler

His work is barely read today, but for several decades of the 20th century Sydney Horler was one of Britain’s most successful writers, and a near-ubiquitous part of the nation’s cultural life.

Born in Leytonstone in 1888, he became a reporter at the age of 17 before serving in the propaganda department of Air Force Intelligence during the First World War. After the war he wrote a novel, a Western titled Standish of the Rangeland, and then football stories, which were serialised in boys’ papers like Chums and Boys’ Realm and a few of which were later published as novels. He also wrote serialised sporting stories for The News of The World before the paper’s editor suggested he try his hand at ‘mystery romances’ – thrillers aimed at a general audience, usually with a love story attached.[i]

The first of these, The Mystery of No. 1, was published by Hodder & Stoughton in 1925 after serialisation in The News of the World, and pushed Horler into the bestseller stakes. The novel’s protagonist, Peter Foyle, is a wealthy young gentleman nicknamed ‘Lulu’ who is visited one morning in his London flat by his uncle, a government minister with a problem on his plate:

‘“We, in the Department, have reason to believe that the greatest criminal gang that this country has ever known, have commenced work in England–”

“Excuse me, sir,” commented “Lulu”, “but have you been beguiling the midnight hours by reading Edgar Wallace by any chance? He’s a topping lad at this sort of thing.”’

Within a few chapters Foyle is on the trail of the gang, a global crime syndicate known as ‘The Order of the Octopus’, whose leader is Dr Paul Vivanti:

‘Of slight – almost childish – build, his huge head dominated his seemingly frail body. It was a remarkable head, bald in front and protruding in a bulge behind – the head of a great genius – or of a great criminal.’

Each member of the syndicate wears a necklace with a seal depicting an octopus and their number within the organisation, Vivanti naturally being ‘No.1’. Chinaman Huan Li Chang heads up operations in the Far East, Count Lasch runs the Central Europe division, and scar-faced gangster Guiseppi Giolatti controls the United States. Together, they have their sights set on ‘the greatest destructive implement that Science has yet evolved’: a new weapon that is able to blow up ‘anything on land, in or under the sea, or in the air’. Aided by an American detective and the beautiful daughter of a vicar, Sylvia Fowke, Foyle infiltrates the organisation and, well, foils their plans. He also, of course, ends up with Sylvia, who he fell in love with at first sight in Chapter Three.

Horler’s reference to Edgar Wallace early in the novel was not an idle one. As well as mildly aiding the illusion that his characters live in the same world as us, as with John Buchan’s reference to Rider Haggard in The Thirty-Nine Steps it’s a knowing wink from author to reader, a signal as to what kind of book we are reading and what kind of author he is. ‘I realise this all sounds a bit like a Wallace story,’ he’s saying, ‘And like you, I know those are implausible fantasies that don’t have much bearing on real life. But also like you, I enjoy stories like that, so I’m going to give you something in a similar vein now – come along for the ride.’

In this way, he was also positioning himself in the thriller firmament. Edgar Wallace was Hodder’s most successful author: they had been publishing him since 1921, and had dubbed him ‘The King of Thrillers’. Wallace was extremely prolific: he tended to write the first few thousand words of a novel by hand before dictating the rest, and in this way produced more than 170 novels, 18 plays, and close to a thousand short stories. It was estimated that by 1928, Wallace was the author of a quarter of all the books published in England, discounting the Bible.[ii]

Horler was determined to follow a similar strategy, as he explained in his 1932 book Writing for Money:

‘A writer of purely popular stories like myself has to be a mass producer. After all, what is a book? You and the man next door, who are sporting enough to choose a Horler, can read one of my novels in a couple of nights at least. What’s that you say? You can’t put it down once you’ve picked it up? Well, there you are! Having liked it, you want another. Besides, the competition to-day is so tremendous that an author has to beat down the opposition by sheer weight of numbers. That was what Wallace did, and his methods apply to lesser mortals such as myself. Why, it wasn’t until my seventh novel was published that the public showed any sign of my being upon the earth. That taught me my lesson. I’d learn them, I said. And every day since I’ve stuck to the resolve.’[iii]

Like Wallace, Horler also dictated his novels, sometimes drafting as many as 25,000 words a week as a result. When Wallace died in 1932, Horler bought both his desk and Dictaphone at auction, and later garnered publicity by claiming that Wallace’s voice had mysteriously appeared on one of the dictation cylinders alongside his own.[iv]

The Mystery of No. 1 set the pattern for much of Horler’s subsequent work: secret weapons invented by genius professors, kidnappings, torture, poisonings, characters adopting different identities, and sudden onsets of amnesia.

Horler wrote over 150 novels, but his prose style and characterisation were clumsy and hackneyed, and his plots often made no sense. They also have very little warmth or wit in comparison to his peers. But this was beside the point, as he and his publishers recognised: there were lots of Horler books readily available, and you knew there would be another published soon. The public gobbled them up.

If you bought a Horler, you knew pretty much what you were going to get. His heroes tend to be wealthy upper-class English bachelors, often brilliant at one or more sport, who are aided by brilliant detectives, ‘cor-blimey!’ Cockney taxi drivers and an uncle or cousin who is an Important Personage in government or intelligence circles. Said hero falls in love with the damsel in distress – usually at first sight – and spends most of the novel mooning over her like a teenager until he eventually rescues her from the clutches of the villain and marries her on the final page. The villain is usually male and described as a demon in human form, the most monstrous and dangerous criminal in Europe, and so on. He tends to head an organisation of crooks, many of whom are outwardly respectable aristocrats: they tend to be ugly and sadistic if female, and effeminate and sadistic if male.

The chief villain is also usually a foreigner: handsome and suave but, damningly, just a bit too suave. In several of Horler’s stories, there is a scene in which the hero walks into a casino or night-club, spots a beautiful Englishwoman deep in conversation with the Dastardly Foreign Baddie, and seethes with jealousy and barely repressed racism. Sometimes it’s not repressed at all. In Horler’s 1931 story ‘The Screaming Skull’, secret agent Martin Lorne watches a beautiful woman dance at a nightclub with an ‘unpleasant-looking gentleman’ with a ‘yellow complexion’. Although jealous, Lorne does not intervene:

‘He didn’t intend to compete with a dago: that came under the heading of The Things Which Are Not Done.’

Prejudice against minorities and foreigners was common in literature of the time, but in Horler’s work it feels closer to the surface than most. There was a lot of casual or implicit antisemitism in British thrillers, for example, but in his 1931 novel Adventure Calling, Horler didn’t cloak his:

‘The pawnbroker, who was so repulsively Jewish, humped his shoulders in an expressive gesture.’

Fictional characters’ views are of course not necessarily those of their author, but here and in many other cases we’re not being given the opinion of a character but of the narrator. Horler also published several non-fiction works in which he made his own views of the world clear, and they were very often identical to those of his protagonists. During the Second World War, he published Now Let Us Hate, each chapter of which was an essay about something he detested.[v] In a chapter about pretentious and egotistical authors, he lays out his view that there is a type of woman writer whose books are ‘merely a pale reflection of her own sex-adventures; metaphorically speaking, she is always undressed and prepared to give all – whether this is worth receiving is a debatable point, of course.’ Horler strongly disliked the depiction of sex in fiction, but for women to write about it really got his goat:

‘But what can one say of the cut-and-come-again bunch, the dreary hacks who can only think of one theme – sex – and who write about it till the cows come home? Trollops in mind as well as in body most of them must be.’ [vi]

Horler also felt that ‘the Higher Critical Gentry’ did not give enough credit to genre writers like himself. Any writer who entertained the masses should, he maintained, be seen as an important figure:

‘He does far more good than the lank-faced “intellectual” who writes 400 closely printed pages about the inhibitions of a sex-obsessed wart who should have been drowned at birth. This sounds farcical, but I am serious; I think there is too much attention given to the morbid, the obscene, the degraded, and the perverted, in the reviews of modern fiction, and that, consequently, we are suffering from a deluge of unhealthy muck which should never have been allowed to see print.’[vii]

One can see an outlet for these views in his ‘Nighthawk’ series, which ran for six novels between 1937 and 1954. The alter-ego of gentleman, journalist and novelist Gerald Frost, Nighthawk robs criminals and leaves a drawing of a night hawk as his card. So far, so The Gray Seal/The Saint. But he is also a vigilante against licentiousness, stealing from society ladies he judges to have loose morals. In the second novel in the series, The Return of Nighthawk (1939), he castigates one Lady Sybil Tremayne as he robs her:

‘“You have ruined many men, smashed up many homes, and generally flaunted yourself in the face of public decency. Now that must stop. You understand me: it must stop!”’[viii]

The Return of Nighthawk: watch out, the sex vigilante’s about

Horler devoted another chapter of Now Let Us Hate to the church. He poured scorn on church leaders around the world for not speaking out early or forcefully enough about the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews in Germany. However, he couldn’t help but add his own antisemitic sentiments:

‘I myself detest a certain type of Jew, who is enemy to any country in which he happens to be – witness the food prosecutions here in England since the war – but that does not alter the argument.’

Attitudes change over the decades, but a good enough story can nevertheless overcome future generations’ qualms. You learn to squint a bit. I remember skimming parts of Dennis Wheatley’s novels when I was a teenager because I wasn’t interested in his ambivalent asides on Mussolini and simply wanted to know how Gregory Sallust was going to get out of his latest scrape.

Horler doesn’t have the same appeal today. Despite being crowded with incident and having ‘Horler for Excitement!’ emblazoned across the jackets, his books were rarely exciting and tend to frustrate instead. No doubt because he was dictating at great speed and doesn’t seem to have revised the results much, most of them read like very rough first drafts, containing huge amounts of repetition, padding and loose ends, with cardboard characters frenetically explaining plot points to each other. Reviewing Horler’s 1927 novel False-Face in The Saturday Review of Literature, Dashiell Hammett noted:

‘Everybody moves around a good deal, using trains, motorcycles, automobiles, airplanes, submarines, secret passages, sewers, and suspended ropes. Most of the activity seems purposeless, but in the end dear old England is saved once more from the Bolshevists.’[ix]

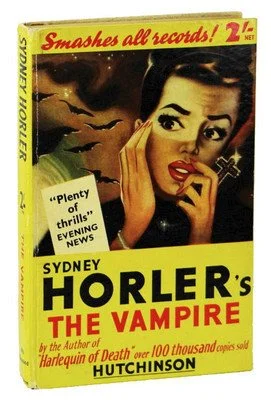

Horler was also a highly derivative writer. He often used the milieus of E Phillips Oppenheim, with many of his thrillers set in the casinos and nightclubs of Monte Carlo and Cannes, but he also freely lifted story premises and scene ideas from others. His 1928 novel The Curse of Doone recycles elements from The Hound of the Baskervilles and several other Conan Doyle stories, while The Vampire from 1935 ‘imitates Dracula almost to the point of pastiche’.[x]

His greatest debt was probably to H.C. ‘Sapper’ McNeile. Horler’s best-known character, Timothy ‘Tiger’ Standish, was so heavily inspired by Sapper’s ‘Bulldog’ Drummond that critic Colin Watson wrote that he could have been Drummond’s twin.[xi] ‘Bulldog’ Drummond is a broad-shouldered former soldier possessed of ‘that cheerful type of ugliness which inspires immediate confidence in its owner’, with a broken nose from boxing at his public school. ‘Tiger’ Standish is a broad-shouldered aristocrat who is ‘attractively ugly’: ‘the right kind of men worshipped him, women adored him’.[xii] When not stopping international conspiracies, Standish plays football for fictional London club The Swifts – in a typical piece of Horler gung-ho, he is known as the ‘most brilliant centre-forward in England and, therefore, the world’.[xiii] There is one key difference between Drummond and Standish: the former works on his own behalf, whereas the latter is a secret agent reporting to Sir Harker Bellamy of British Intelligence.

Another major influence for Horler was Anthony Hope’s 1894 best-seller The Prisoner of Zenda, in which a dashing young British gentleman visits the fictional nation of Ruritania and is persuaded to impersonate its king-in-waiting due to the two men being near doubles. Horler used several permutations of this set-up. Princess After Dark (1931) follows the gentleman-and-a-detective template of The Mystery of No. 1: Philip Wendover, a handsome young gentleman who has inherited a fortune, teams up with a Scotland Yard detective to track down a suave crook named Charles Zuberra and his partner Sybil Trent. The two have taken under their wing Elsie Spain, an innocent young shop girl who just so happens to look identical to the princess of ‘Caronia’, widely presumed to be dead.[xiv]

The novel ends with Wendover rescuing Elsie from an asylum, strangling Zuberra to death after a brief car chase, and marrying Elsie. It ends in the cheesiest fashion imaginable:

‘She looked up into his face.

“If you want to say it, Philip, you can,” she encouraged.

There were tears in her eyes, and he endeavoured to drive them away. And so the word which he had sworn should never pass his lips was uttered.

“But you're a Princess,” he gently mocked.

She went to the arms that were outstretched. And in that safe anchorage made her reply.

“A Princess! But only after dark! I was a sham, a lie.... Let me be just a woman, Philip!”

He closed her lips with a kiss.

“You shall,” he said; “my woman.”

Another case of Zenda-like antics can be found in Horler’s 1932 novel High Stakes. This opens with British agent David Ashton, ‘Y.13’, being strangled in his compartment on the Orient Express by his doppelganger, who throws him from the train and then takes his place so he can find the secret plans for a new weapon. Ashton improbably survives strangulation and being chucked out of a train at high speed, but apart from the usual injuries this also triggers amnesia. Once he has remembered who he is, he turns up in the final chapters to impersonate his evil double and save the day.

A lot of Horler’s work features espionage. Following the success of The Mystery of No. 1, he wrote several more novels featuring Peter Foyle, but also created other characters in a similar vein, of which Tiger Standish was one: these handsome, wealthy and upper-class Englishmen work either freelance or full-time as secret agents for British intelligence. Occasionally they are half-American, presumably to broaden the books’ appeal to readers in the United States. One such character is Brett Carstairs, who appeared in The Spy, published in 1931, also titled The Man Who Walked With Death. Like The Scarlet Pimpernel or Jimmie Dale before him, Carstairs appears to the world at large to be a careless playboy but has another role: in reality, he is Britain’s ace intelligence operative.

Another of Horler’s characters in this mould was Buncome ‘Bunny’ Chipstead, who appeared in four novels between 1927 and 1940. And I believe it is this series that Eric Ambler drew on directly when writing The Dark Frontier. I’ll dig into that in the next chapter.