Tradecraft

This is a section of Need to Know. You can download the whole book in the format of your choice here, or read the articles individually directly on this website. Just click on the item below that you would like to read, or return to the main Table of Contents here.

Introduction

This is part of Tradecraft, a section of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

In my twenties, I found myself living in Brussels and working as a journalist for an English-speaking magazine, The Bulletin. Its readership largely consisted of expatriates working for the European Union institutions, and the average length of time they spent there was less than three years. It seems Eurocrats have a taste for spy novels, because the shelves of the city’s second-hand bookshops were heaving with paperbacks by Len Deighton and others that had been dumped as their owners moved on to new assignments. As a boy, I’d stayed up many a night engrossed in The KnowHow Book of Spycraft—as I picked my way through the bookshops of Brussels, I became a devotee of spy thrillers.

Eventually, I considered writing a spy novel of my own, set in the Cold War. In the meantime, I continued with my day job as an editor and writer at The Bulletin. I wrote about a wide variety of subjects, but whenever possible I tried to pursue stories with espionage angles, or that I thought might help with the background for my novel. The first article in this collection, Whisper Who Dares, published in June 2005, is an example of this. I hadn’t known that the SAS investigated Nazi war crimes after the war, and writing this piece led me to research the topic further. That eventually fed into my novel, which I titled Free Agent and which was published in 2009.

I’ve written several more books since then, and quite a few articles along the way. In this collection, you’ll find 20 pieces I’ve written for newspapers, magazines and for my own website, and if you’ve read any of my books you’ll see how some of them inspired topics and themes in them.

The second piece, Rendezvous With a Spy, is an exception in that it’s previously unpublished. It also has a Brussels connection, as it happens. This dates from 2011, when I was writing Dead Drop (Codename: Hero in the US), my non-fiction book about MI6 and the CIA’s joint operation to run agent-in-place Oleg Penkovsky in the early Sixties. I had planned to write the book with my own footsteps following the operation as a focus, but one strand I’d written in that vein unbalanced the tone of the rest of it and so I cut it. I think that was the right decision for the book, but I remain fond of this as a piece of writing in its own right. I’ve left in a few sentences that made it into the final version of the book for context, and hope it gives some interesting insight into the research process as well as what makes spies and intelligence officers tick. Pete Bagley died of cancer at his home in Brussels in February 2014.

From the inner sanctum of a former CIA officer, let’s head into the world of British spookdom. The Spies We’ve Loved is an overview of spy fact and fiction I wrote for The Sunday Times in June 2009 to coincide with the centenary of the British intelligence services being established.

Several topics and themes I discuss in this piece will crop up in other ones. One is a focus of the next four articles: propaganda. The first combines two articles, both originally published on my website (Close Encounters in May 2011, and The War of Ideas in May 2013), in which I look at how MI6 and the CIA tried to influence public opinion during the Cold War by surreptitiously using writers. When Julian Met Graham and Secreted in Fiction (published on my website in March and September 2013) both deal with the Russian spy novelist Julian Semyonov, and the ways in which he tried to subvert the KGB’s grip on the narrative. And Spies of Fleet Street is an article I wrote for the BBC’s website in March 2013 to accompany a programme I wrote and presented for Radio 4 about how MI6 used journalists.

A couple of lighter pieces are up next: A London Spy Walk was first published in Time Out London in May 2009, while I wrote Top Ten Spy Gadgets for The Times the same month. In From The Cold is a review of the late Keith Jeffery’s official history of the early years of MI6, published in The Mail on Sunday in November 2010.

A version of Paperback Writers was first published on my website. I wrote the article in 2002, and it features interviews with Martin Cruz Smith, John Gardner, Donald Hamilton and William Boyd. The first three I essentially just called up after tracking down their numbers, while I interviewed Boyd in person as part of my day job while he was promoting Any Human Heart. I’ve tweaked a few sentences in the article, but left its description of the spy fiction scene as it was at the time. Few of the film projects mentioned panned out, and sadly John Gardner and Donald Hamilton are no longer with us, but this is a chance to read rare interviews with both of them, and journey back to the world of vintage spy paperbacks.

Published on my website in February 2011, From Sweden, With Love is an interview with the thriller aficionado and muse Iwan Morelius. Iwan died in 2012—I named a character after him in Spy Out the Land in tribute.

From February 2009, Deighton at Eighty is an article I wrote for The Guardian paying tribute to the great Len Deighton on his 80th birthday. This is followed by my interview with Deighton expert and biographer Edward Milward-Oliver, which was published on my website in April 2013. It has a brief update appended.

I interviewed the spy novelist Joseph Hone in 2002 with the intention of including him in Paperback Writers, but for various reasons he didn’t quite fit there. The Forgotten Master of British Spy Fiction was first published on my website in March 2010, and became the basis for my forewords to new editions of Hone’s novels published by Faber Finds in 2014. If you haven’t read him yet, I can’t recommend him highly enough.

As can be seen from many of the previous articles, it’s virtually impossible to write about spies and ignore the influence of James Bond on the genre—even John le Carré was a little fixated by the character. I’m no exception, and the next few articles are something of a Bond buffet.

Waiting for Deaver is an article I wrote for The Daily Telegraph in May 2011 on the eve of publication of Jeffery Deaver’s James Bond novel Carte Blanche, looking at how Fleming’s reputation has changed over the decades.

From the same month, The Lives of Ian Fleming is a piece I published on my website on two excellent biographies of Bond’s creator, by John Pearson and Andrew Lycett. When William Met Ian delves into a rare interview between Ian Fleming and his editor William Plomer, and was published on my website in September 2015. A Letter from ‘008’ is the most recent piece here, first published on my website in October 2015, and as well as being a curio on Fleming is about how technology is easing research and changing our perceptions as a result.

Finally, in Licence To Hoax I look at another Fleming biographer, but one who put his interest in espionage fact and fiction to more unethical use than one might expect. This article was first published on my website in December 2014.

So there we are: 20 articles on spy fact and fiction from my career to date. I hope you enjoy them as much as I did researching and writing them.

Jeremy Duns

Mariehamn, February 2016

Whisper Who Dares

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

Jacques Goffinet, 1945

‘Yes, I wanted vengeance in 1945. But if I had killed the Nazis I tracked down, that would have made me as bad as them, wouldn’t it?’

Jacques Goffinet is speaking to me on the phone from Reguisheim in France. Sixty years ago yesterday, aged just 22, he arrested Germany’s foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, in Hamburg. Tracking down Nazi war criminals was his final job after four years as a member of one of the Allies’ most successful units: the Belgian SAS.

Britain’s Special Air Service—motto ‘Who dares wins’—is regarded as one of the world’s greatest fighting forces, and there have been hundreds of books, articles and films about its exploits. But very little attention has been given to its Belgian squadron.

It started life in 1942 as the Belgian Independent Parachute Company, in Malvern Wells in western England (about 30 kilometres from Hereford, where the SAS is now based). The BIPC. was mainly made up of soldiers who had escaped from occupied Belgium and Belgian volunteers from the US and Canada. It included men who had been farmers, lawyers and dentists—as well as three barons.

The company was led by Eddy Blondeel, a former engineer from Ghent nicknamed ‘Captain Blunt’. Despite the difficulties of leading a multi-lingual group, Blondeel commanded the absolute respect of his 130 or so men. They learned parachute jumping, hand-to-hand combat and sabotage techniques at various locations, including Inverlochy Castle in Scotland, where they trained alongside members of the SAS.

The SAS had been set up in 1941 by British officer David Stirling with the intention of wreaking havoc on the Nazis in northern Africa: it consisted of small commando units, who were usually parachuted behind enemy lines.

In February 1944, the B.I.P.C. moved to a training camp in Galston, near Ayr, where it was merged into the SAS. Although a relatively small brigade, 5 SAS, as it was now known, was not some obscure wing of the regiment: it completed several crucial missions. Some of its operations involved just a handful of men being dropped into France, after which they would sabotage the Germans’ communications or blow up bridges. Some involved the entire company—Operation TRUEFORM in August 1944, for example, when, along with British SAS, they landed in Normandy and inflicted substantial damage on the retreating German armoured columns, who were trying to cross the Seine. Others still were long-term missions: Operation FABIAN was carried out by five Belgian SAS members from September 1944 to March 1945, near Arnhem in the Netherlands.

FABIAN was led by one of the first members of the Belgian SAS, Gilbert Sadi-Kirschen, who spent much of the war using the alias of `Fabian King’. The son of the barrister who had defended Edith Cavell in a German military court in World War One, Sadi-Kirschen qualified as a lawyer himself, but when war broke out, joined the Sixth Artillery Regiment. When Belgium surrendered, he, like many others, was arrested, and was put in a truck to be taken to a POW camp. He escaped from the truck, and travelled through France, Algeria, Tangier, Portugal and Gibraltar, being imprisoned for two months on the way, before finally making it to England, where he joined the Belgian parachutists. The aim of FABIAN was to find the locations of the Germans’ V2 rocket launch sites: it was meant to last eight days, but ended up taking six months.

Sadi-Kirschen also led Operation BENSON, in which a six-man team jumped near Beauvais in north-eastern France in August 1944. A couple of the men suffered minor injuries on landing, and were taken to a doctor trusted by the local Resistance. The doctor told them that the previous day he had been sitting in a café with a German major, and had sketched down the map the man had left on his table when he went to the bathroom. The sketch was very simple—but showed every German division on the Somme, and even the position of Army Headquarters.

The SAS men immediately retreated to a barn to transmit the information, but were interrupted by Germans using a self-propelled gun. Quickly hiding their sets, they escaped from the barn, and took cover under some corn-stacks in a nearby field. The Germans searched frantically for them, but gave up once it got dark. The SAS team returned to the barn, rescued their sets, and made their transmission. It was one of the major coups of the latter stages of the war.

Members of the Belgian SAS were the first Allied troops to set foot in Belgium, and the first SAS unit to enter Germany. When one considers all the information they received and all the damage they caused the Germans, it’s by no means far-fetched to say that the they made a substantial contribution to the Allied victory. Their success rate was phenomenal, and by the war’s end, only 15 men of the unit had been killed. One of these was Corporal-Signaller Raymond Holvoet, who was captured, tortured and finally executed by the Germans in April 1945, in Zwolle, in the Netherlands. Three years earlier, Hitler had issued his infamous Kommandobefehl, or Commando Order, in which he stated that Allied special forces would not be afforded the terms of the Geneva Convention—any member of an enemy ‘sabotage unit’ captured alive would be shot.

For many in the SAS, this was a step too far. In the closing stages of the war and in the months following it, British and American counter-intelligence groups began tracking down and arresting Nazis suspected of war crimes. After the liberation of Brussels, some members of the Belgian SAS were attached to these groups. They travelled across Europe, and arrested many leading Nazis, including Admiral Karl Doenitz, the commander of the German navy and, for 20 days following Hitler’s suicide, Germany’s president; Alfred Rosenberg, the minister for the eastern occupied territories; and Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Nazis’ foreign minister.

‘It was a tough job,’ says Jacques Goffinet with typical understatement. Post-war Germany was an anarchic place: liberated P.O.W.s and refugees lined the roads, food and drinking water were scarce and electricity and gas often unavailable. In some of the cities, sewer lines ran into bomb craters and bodies rotted under the debris of destroyed buildings. Neither did peace mean an end to violence: Russian agents were combing D.P. camps hunting down and executing `traitors’ to the Soviet Union, and some soldiers and civilians were conducting their own searches for enemies to avenge. Members of the British Army’s Jewish Brigade assassinated several Nazis around this time.

As a sergeant in the Belgian SAS, Goffinet had taken part in operations CHAUCER and NOAH. Now he was assigned to a British counter-intelligence operation in Hamburg. On the morning of June 15 1945, he arrived at headquarters as usual. Two German civilians were waiting outside the building—they told him that they knew von Ribbentrop was hiding out in an apartment in Hamburg, using the name Von Riese. They gave him the address.

Goffinet wasn’t hopeful—most such leads were dead-ends—but together with a British lieutenant called Adams and a couple of colleagues, he set out for the apartment. The door was locked, but as Goffinet began to try to prise it open, it was opened by a woman in a nightdress. Coming into the bedroom, Goffinet and his colleagues surprised a sleeping von Ribbentrop, who was wearing silk pyjamas. He knew at once that the game was up, and didn’t try to flee. Goffinet checked that he didn’t have a cyanide capsule under his lip and removed a razor from him as he packed. Hidden in the apartment was 200,000 marks and a rambling letter to ‘Vincent Churchill’ blaming the British for ‘anti-German bias’.

Von Ribbentrop was found guilty at Nuremberg the following year and hanged. Considering the execution of Raymond Holvoet, I ask Goffinet if he was at all tempted to hand von Ribbentrop his fate himself. ‘No,’ he says. ‘He was just another Nazi to me.’

The Belgian SAS eventually ‘returned’ to Belgium, where they were based in Tervuren. Blondeel faced many difficulties in keeping such a specialised force operating in a small country in peacetime, and the squadron was merged with the paras. In 1952, the paratroopers and the commandos merged into one regiment, which remains the case today. Belgian SAS veterans, of which there are now around 60, are still very active, though. As well as their own newsletter, they meet up at their club in Brussels once a month, and hold an annual ‘Blunt Lunch’ in honour of their commanding officer, who died in 2000, aged 93.

Jacques Goffinet is about to go into a nursing home. He tells me he rarely thinks about his days in the Belgian SAS, but seals it off in a compartment in his mind. I ask him why he thinks his old squadron is not as well known as some of the others, despite its extraordinary achievements. He laughs, and I try to imagine the face of the intense-looking 22-year-old in the photographs I’ve seen at 82 as he answers. ‘Perhaps we’re just modest,’ he says.

With thanks to Des Thomas, Marc Backx, Paul Marquet and Jacques Goffinet

Rendezvous with a Spy

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

Pete Bagley

I had imagined it would be raining in Brussels, but as I step out of the airport terminal I find myself blinded by bright sunshine. When I lived here years ago I had longed for days like this, but now I’m slightly disappointed: it feels like the wrong weather for a rendezvous with a spy.

I find a taxi and the driver speeds me through the streets, past drab factories and glass-encased office complexes. As we reach the city centre, the familiar hodge-podge of architectural styles flits by: a brown monstrosity from the Sixties, soot-stained Art Nouveau villas, a modern hotel in marble and granite, and then a run of pharmacies, kebab restaurants and photocopy shops. My cabbie, conducting an argument with someone through his Bluetooth earpiece, takes a stomach-churning swing of the wheel and guns up a wide tree-lined boulevard. We are now in the diplomatic quarter. I catch sight of a bloom of red roses in an otherwise sparse garden, the flag of a South American nation hanging from elaborate cornices above.

A few minutes later, we reach a quiet crossroads with a flashy-looking Italian café positioned on one corner, customers in sunglasses smoking and drinking beer by the side of the road, squinting at their smartphones and laptops. I pay my taxi driver and walk to the block of flats directly opposite the café.

It is a squat building encased in dark grey brickwork: not beautiful, but not especially ugly either. That, at least, feels right. Because unknown to the Eurocrats sipping Hoegaarden behind me, this nondescript building is home to secrets. The present is unspooling in the sunshine, but I am about to journey back in time, deep into the heart of an espionage operation that changed the course of the Cold War fifty years ago.

I click the door open and walk into the foyer. A bank of buttons has names printed on it, and one of them reads ‘Bagley’. I push it, and a few seconds later a speaker crackles with static. ‘Good morning!’ says a tinny voice. ‘Come up.’ I step into the tiny lift and wonder what I will find when I emerge from it. It has taken me weeks to set up this meeting, and Tennent Harrington Bagley—known to most as Pete—has offered to talk to me for several hours.

I’m nervous. I have spent years researching the Cold War for my spy novels, and Pete Bagley has featured in several of the books on my shelves. Now 85, he is one of the few survivors of the upper echelons of the CIA who battled against the KGB, and has been described as ‘a legendary spy’. He was appointed deputy head of counter-intelligence in the CIA’s Soviet Russia division in 1962 at the tender age of 30. According to one former colleague, there were few in the agency more ‘nakedly ambitious’, while CIA director Dick Helms has said he was a ‘golden boy’ who was seen as a potential future head of the agency.

But Bagley never made it to head of the CIA: instead he became embroiled in a controversy that nearly tore the agency apart, and he ended his espionage career as Chief of Station in Brussels, where he has long since retired. That controversy, the handling of the defector Yuri Nosenko, has featured in several books and films, including a 1986 BBC/HBO production in which Tommy Lee Jones played a fictionalized version of Bagley, ‘Steve Daley’, and Robert De Niro’s 2006 film The Good Shepherd.

In 2007, Bagley wrote a memoir focusing on the Nosenko operation, but at several points his account intersected with another story. The handling of Russian colonel Oleg Penkovsky, codenamed HERO, had the highest stakes of any operation ever run by either agency. Taking place during two of the most dangerous episodes in recent history—the Berlin crisis in 1961 that led to the building of the Wall and the Cuban missile crisis of 1962—the operation was packed with human drama, as well as espionage tradecraft familiar to millions from fiction: microfilmed documents, assignations in safe houses in London and Paris, and coded messages and dead drops in Moscow. If it sounds like the plot of a John le Carré novel, this is no coincidence: it inspired one of his best-known books, The Russia House.

I have long been fascinated by Penkovsky and the unanswered questions, conspiracy theories and Chinese whispers that have surrounded the operation, and I looked at it in greater detail when researching a novel set in Moscow during the Sixties [The Moscow Option]. Pete Bagley’s memoir, although primarily about another operation, seemed to me to present new evidence about Penkovsky that warranted further investigation. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Bagley had taken advantage of the new spirit of openness to travel to Russia. He met with several former KGB officers with whom he had fought invisible battles for years, and in time became friendly with a few of them. The days of openness were all too brief, and the door soon shut on many such exchanges, but Bagley had found some answers, and he detailed them in his memoir.

Some of the information was simply staggering. Bagley claimed that former Soviet intelligence officers had told him that the KGB had discovered that Penkovsky was working for the West earlier than they had claimed: the official story was bogus. Bagley wrote that Penkovsky had most likely been betrayed by a double agent working for the Soviets in the West, perhaps a very high-ranking member of CIA or MI6.

I’ve read a lot of books about espionage, and many contain outlandish conspiracy theories, but Bagley’s book stayed with me for months. I realized that it was not simply a matter of detail about a half-century-old espionage operation: Penkovsky’s information is credited as having helped Kennedy face down Khrushchev during both the Berlin and Cuban crises. If Bagley’s claims were true, they had a knock-on effect on both those events for a simple reason: if the KGB had known throughout that a military intelligence officer was giving the West highly classified military secrets, why had they let him continue to do so—and how had it altered their own actions? In short, Bagley’s information had the potential to change the accepted history of two of the major events of the 20th century, both of which had nearly led to nuclear war.

I began reading other material about Penkovsky, a lot of which has been declassified in recent years, and Bagley’s theories became harder to dismiss. In particular, one point he had spotted that is already in the public domain seemed irrefutable, and completely overturned the established version of events. But other information in his book, such as that from former KGB officers, was frustratingly attributed to anonymous sources. I decided I had to see him to find out more.

The lift doors shudder to a standstill and I step out into a narrow corridor. Bagley has ‘vetted’ me in several long phone calls and emails before agreeing to see me, asking a series of questions to test my knowledge about the topic, my journalistic techniques and more. He has strongly hinted on the phone that he might now reveal the names of some of his sources to me, and precisely what they told him—but what if he has had second thoughts, and decides to clam up?

A door to my left is ajar, and I glimpse a parquet floor covered by several Oriental carpets. Pete Bagley steps forward. He is a still-handsome man, standing tall in a light blue button-down shirt, grey flannel trousers, and polished brogues a deep burgundy colour. His crisp white hair is smartly cut and his face is tanned. We shake hands, and he quickly ushers me through the living room and into a darkened study. The walls are decorated with framed prints and photographs, many of which have a maritime theme. Bagley is from a famous naval family—born in Annapolis, his father was an admiral, as were both his brothers and two of his great-uncles. Bagley enlisted in the Marines in 1943 aged 17, and after the war studied political sciences, taking a Ph.D at the University of Geneva. In 1950, aged 25, he joined the CIA.

Apart from the naval theme, the room is a kind of Cold War cocoon, and strangely familiar to my own study. I recognize many of the books in his shelves from my own, only the spines of his have handwritten reference numbers taped to them: his own private library system. Most of the books are non-fiction, but there are also some novels by John le Carré and Alan Furst. On top of a filing cabinet I spot a paperback of my first novel, and my palms feel a little sticky: more vetting. Behind a sturdy desk, home to a computer and copious piles of paper, are further bookshelves, some of which are taken up with large blue binders. ‘My archives,’ he smiles, seeing me spot them. ‘I’m going to tell you about what’s in some of them today.’ He points to a low gold-coloured sofa. ‘Please, take a seat.’

I am here to interview Pete Bagley, but at times it feels like he is interviewing me: trying to eke out answers from a man trained to do the same with others is not always easy. He speaks in a quiet sing-song voice, almost professorial in tone, and every often he lobs a question of his own into the conversation, about certain books, or certain operations, checking for my reactions. I weigh my words very carefully, conscious that he might at any moment decide that I’m not the person to talk to after all.

Bagley’s replies are equally careful, but his recall of names, dates and facts from decades ago is remarkable. As we circle each other and the reason I have come here, I sense that he misses the old days, when he was involved in the highest echelons of the espionage game. At several points his eyes film over when he mentions officers he knew who have died.

After around an hour of discussion, he tells me he has booked a table for lunch nearby, and we take the lift down to the street and walk a few blocks until we reach a large townhouse that has been converted into a restaurant, and which also acts as the clubhouse for a local tennis club.

We walk through a dark vestibule and a waitress spots us and rushes over. ‘Ah, Monsieur Bagley, comment allez-vous?’

‘Très bien, merci,’ he replies, and she leads us to a table near the windows. Once she has left, Bagley asks me if I think the location is okay. ‘She said it was a little windy outside, and I’m not so sure, but this has a nice view and its position means we can talk undisturbed.’

I smile at the small piece of tradecraft. Old habits…

We take our seats and order, both of us going for the plat du jour, and continue our discussion, still feeling each other out. I gently probe to see if I can persuade him to reveal more about the sources for some of his information on Penkovsky. Bagley’s memoirs were primarily about another Soviet agent-in-place, Yuri Nosenko, but the Penkovsky and Nosenko operations overlapped in several intriguing ways, and it’s this I want to discuss. Our dishes arrive, and Bagley looks up for a moment and stares into the middle distance.

‘I’m dying,’ he says suddenly, his tone matter-of-fact. ‘My doctors have given me a few weeks. I don’t know if they’re right this time—they’ve said it before—but they could be.’

I look at him, stunned. He seems a picture of health, a pink glow under his unlined tanned face, and apart from the whiteness of his hair could be a spry 60-year-old about to play a game of tennis here.

‘I’m very sorry to hear that,’ I manage.

‘Oh,’ he says, waving his hand. ‘It’s not the end of the world. Well, it’s the end of my world, maybe.’ He smiles ruefully at the poor joke. ‘I only mention it to underline that there is perhaps a little more urgency to these matters, and to our meeting.’

I stare down at my blanc de volaille. The moment passes, and Bagley continues talking. ‘So you wanted to know about Zepp,’ he says…

Now read on in Dead Drop

The Spies We’ve Loved

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

In the spring and summer of 1909, Colonel James Edmonds presented himself at a sub-committee of the grand-sounding ‘Committee of Imperial Defence’ in Westminster. Although nominally head of Britain’s military counter-intelligence, Edmonds’ budget was tiny and he only had two assistants—most intelligence was still being gathered by the Admiralty, the War Office and the Foreign Office. But this sub-committee had been convened to analyse the threat of a German invasion, and Edmonds saw his chance. Over the course of three secret sessions, he made the case that Britain was all but over-run with German spies, presenting detailed information about suspicious barbers and retired colonels plotting dastardly deeds across the land.

When this failed to convince the committee, a dramatic document arrived at the War Office at the last minute. It was said to have been discovered by a French commercial traveller who had shared a compartment on a train between Spa and Hamburg with a German who had happened to be carrying a similar bag. The German, it was claimed, had disembarked with the wrong bag. When the Frenchman perused the one he had left behind in the compartment, he discovered ‘detailed plans connected with a scheme for the invasion of England’. This pushed the sub-committee over the edge: a few weeks later, it recommended to the prime minister the creation of a Secret Service Bureau, divided into two sections, Home and Foreign. These sections would later split, and become known as MI5 and MI6.

If the idea of the country being overrun by German agents sounds like the stuff of spy novels, that is because it was. In a desperate bid to stop the police from taking over what he saw as his rightful domain, Edmonds had brazenly taken many of his ‘cases of German espionage’ from a novel called The Spies of The Kaiser. This had been written by a friend of his, William Le Queux, and had been published a few months earlier. The mysterious document discovered by the French commercial traveller also has all the hallmarks of a Le Queux story.

Spy fiction, then, played a key role in the birth of Britain’s intelligence apparatus. In the century since, this curious relationship has continued, with spy novels often reflecting real-life espionage events and occasionally, as in 1909, influencing them.

The First World War was not much of a success for the Secret Service Bureau, nor any other intelligence agency in Europe for that matter. Most discovered to their cost that it was relatively simple to discover the location and strength of the enemy’s forces, but extremely difficult to gauge what they planned to do with them. Spy fiction prospered during the war, though: Le Queux, John Buchan, E. Phillips Oppenheim and others turned out a stream of thrilling if implausible tales of gentlemen heroes who save England from dastardly plots.

It was not until the 1920s that the genre would receive its first dose of reality. This came from Somerset Maugham, whose short stories about British writer-turned-agent Ashenden were the first to present espionage as a rather shabby occupation, filled with loose ends and frustrating bureaucratic muddles. Ashenden is sceptical of the spying game from the start, when a colonel in British intelligence known only as R. tells him about a French minister who is seduced by a stranger in Nice and loses a case full of important documents as a result. Ashenden laconically notes that such events have been enacted in a thousand novels and plays, but R. insists that the incident happened just weeks previously. Ashenden is not impressed, remarking that if that is the best the Secret Service can offer, the field is a washout for novelists: ‘We really can’t write that story much longer.’

Maugham had personal experience of the espionage world, having worked for British intelligence during the war. But his greatest follower in this new school of spy fiction had no such background, having worked as an advertising copywriter. This was Eric Ambler, whose centenary will also be celebrated this year: on May 28, five of his novels will be reprinted as Penguin Modern Classics.

Ambler brought a new psychological dimension to the genre, and in novels such as The Mask of Dimitrios and Epitaph for a Spy he exposed the murky underworld of European politics and finance. His 1930s novels were also dominated by the spectre of the coming war—but he was not the only one to see the writing on the wall. Published just a few months before the war began was Rogue Male by Geoffrey Household. This is arguably the forefather of the modern action thriller: a British gentleman tries to shoot an unnamed dictator, fails, and is pursued by enemy agents across the English countryside. Like Ambler, Household looked beyond the simplistic vision of good and evil of earlier novels, as well as introducing a dose of physical toughness to the genre.

Household’s unnamed narrator acts not out of patriotism, but principle. Once war had been declared, though, the genre would again struggle to make that distinction. The blackout created a huge demand for escapist reading material, and one of the first to capitalize on this was Dennis Wheatley. His thriller The Scarlet Impostor was published on January 7 1940, making it the first spy novel to be set during the Second World War.

Wheatley was firmly in the Le Queux and Buchan school of scrapes and fisticuffs. In order to make his baroque plots more believable, he also used brand names on a grand scale—the first thriller-writer do so. In The Scarlet Impostor, British agent Gregory Sallust is on a mission to make contact with an anti-Nazi movement in Germany. During the course of the novel we learn that he smokes Sullivans’ Turkish mixture cigarettes, drinks Bacardis and pineapple juice, carries a Mauser automatic and has his suits made by West’s of Savile Row. The romantic vision of the spy had returned with a vengeance.

Wheatley spent the war balancing the fictional and real worlds of intelligence. While still regularly publishing thrillers, he was a member of the London Controlling Section, a team within the Joint Planning Staff of the War Cabinet dedicated to planning deception operations against Germany (such as Operation MINCEMEAT—‘The Man Who Never Was’—and Montgomery’s double). His novels of the time are curious mixtures of thrilling potboilers packed with up-to-the-minute analysis of the politics of the time.

With the end of the war, the Soviets became the new enemy, and it was felt that new methods were needed to defeat them. The Special Operations Executive—‘Churchill’s secret army’—was rapidly disbanded and replaced by the Secret Intelligence Service, more commonly known as MI6.

While a new breed of professional secret agents were trained and sent into the field, the spy novel was also changing. The genre had long been dominated by male writers, but after the war female spy writers emerged, notably Helen MacInnes and Sarah Gainham. But the big development came in 1953, with the publication of Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale. With his Balkan cigarettes, vodka martinis and Savile Row suits, Fleming’s James Bond was a Gregory Sallust for a new age: the age of the Cold War.

In 1962, the first Bond film was released, and Britain’s fictional spies dominated the rest of the decade. Britain’s real-life intelligence community, however, was in disarray: paranoid, disillusioned, and turning on itself. This was the result of the discovery of an alarming number of double agents operating in its ranks, most notably the Cambridge Ring. As the extent of the deception became clear, spy novelists turned away from the fantasy of Bond. Led by Len Deighton and John le Carré, plots increasingly revolved around the hunt for these ‘moles’—a term coined by le Carré but later adopted in intelligence circles. Like Maugham and Greene before him, le Carré had first-hand experience of espionage, and was able to give readers the impression they were privy to the inner workings of the spy world.

The genre had again turned from gung-ho physical action to the darker world of human psychology. In the Seventies, the more realistic school of Deighton and le Carré gave way to fantasy once more—albeit fantasy presented as realism. Frederick Forsyth emerged as the inheritor of Fleming, with plausible but highly melodramatic thrillers that paved the way for a new field called ‘faction’. Thriller-writers began to explore the Second World War in earnest, and for the first time Nazis were portrayed in an empathetic light (in Jack Higgins’ The Eagle Has Landed and Ken Follett’s The Eye of the Needle, for example).

During the Seventies and Eighties, the real world of espionage sometimes seemed more extraordinary than its fictional counterparts. A Venezuelan terrorist-for-hire eluded the world’s security forces in a way that would have made Eric Ambler’s Dimitrios gasp—he was even dubbed the Jackal by the press after a copy of Forsyth’s most famous novel was said to have been found among his possessions. In London, the dissident Bulgarian writer and broadcaster Georgi Markov was poisoned with a ricin-tipped umbrella as he walked across Waterloo Bridge. A thousand would-be spy novelists picked up their pens—but as Alexander Litvinenko’s murder in 2006 shows, such techniques were not a one-off, and have not disappeared.

As the Cold War wound down, so too did the spy novel. Innovations included forays into speculative fiction (Robert Harris’ Fatherland) and new territories (Martin Cruz Smith’s Gorky Park, while not strictly a spy novel, certainly felt like one). Deighton retired and le Carré moved on to new subjects. But eventually the genre rose from the ashes, in new forms. Robert Ludlum’s frantic conspiracy thrillers and David Morrell’s brutal action novel First Blood—inspired by Household’s Rogue Male—led to the SAS adventures of Andy McNab and Chris Ryan in the Nineties, and Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code in 2003.

In this decade, the spy story has flourished: on television and in cinemas, Spooks, 24 and the Bourne films are reflecting the current reality, while novelists such as Charles Cumming, Henry Porter and Tom Cain explore it in print. Meanwhile, writers such as Alan Furst and Tom Rob Smith shed new light on espionage history—I hope to do the same with my own novels set in the Cold War. Nobody can know what will happen in the next century of espionage, but one thing is for certain: spy novelists will be there to tell the story.

First published in The Sunday Times, 17 May 2009

The War of Ideas

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

‘The propagandist writes solely with the intention of appealing to his readers’ interest. He aims to hit, because he cannot afford to miss.

Accordingly his work is based on the formulae of modern advertising, to whose task his own runs broadly parallel.

It differs only in that the propagandist is at greater pains than the copywriter to disguise his medium. The reader of an advertisement should never be provoked into feeling: “This is only an advertisement.” The reader of propaganda should, if possible, never be allowed even to suspect that he is reading propaganda.’

These words, written in April 1943, are contained in the syllabus used at the Special Training Schools of the Special Operations Executive, which were declassified in 2001. Variations of the same text were used in different schools, and this comes from the syllabus used by STS 103 in Canada, also known as Camp X, where members of SOE and OSS were trained together.

As this was document was used to train secret agents, its authors names do not appear anywhere in it, but we now know that two senior SOE instructors wrote it: Paul Dehn and Kim Philby. Dehn, a poet and novelist, became a well-known scriptwriter after the war, working on the screenplays of both The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and Goldfinger. Philby went on to rise through the ranks of MI6 and was tipped by many to head it, but was eventually exposed as being a double agent working for the Soviets, having been recruited while a student at Cambridge University in the 1930s.

There is a chilling irony in the fact that Kim Philby was one of the writers of the syllabus used to train British secret agents during the war—and one has to wonder how much of it might be propaganda.

This is what James Jesus Angleton famously referred to as the ‘wilderness of mirrors’ that populates espionage. Even when being taught about propaganda, I may be subject to it.

In October 1953, a new monthly magazine was launched in Britain: Encounter. An Anglo-American publication, it was a literary magazine that also dabbled in politics: it was liberal but broadly anti-Communist. Its first editors were Irving Kristol and the poet Stephen Spender and it was funded by the Paris-based Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF). It soon became very influential, publishing the work of many of the most famous writers and thinkers of the day, including WH Auden, Vladimir Nabokov, Iris Murdoch and Bernard Russell. But in 1967, it was revealed that the CCF was a CIA front, and that most of the finances for the magazine had come straight from the CIA’s coffers, with the remainder being provided by the British Foreign Office’s innocuously named Information Research Department—a secret propaganda group.

This isn’t a conspiracy theory, but fact, as the CIA itself now acknowledges. Stephen Dorril also discusses it at length in his excellent book, MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. The idea for the magazine grew from meetings between MI6 and the CIA, who wanted a way to influence the thinking of the liberal intelligentsia in Britain. The mastermind behind the idea was CIA officer Michael Josselson, a former member of the US Psychological Warfare Division. On the British side, the two leaders of the project were initially Tosco Fyvel, a member of the IRD who had been a close friend of George Orwell, and Malcolm Muggeridge, a senior journalist at The Daily Telegraph who also worked for MI6 ‘part time’. Muggeridge eventually grew disillusioned with the way the behind-the-scenes machinations and withdrew from the project. He was replaced by Goronwy Rees, another MI6 agent. But we now know that before the war Rees had passed information to the Soviets, who had given him the codenames FLEET and GROSS.

To ensure that Encounter’s propaganda was effective, its audience could not perceive that it was propaganda. As a result, the CIA and MI6 left the majority of the content alone. That way, the magazine established itself, and was taken by British intelligentsia as a genuine and unadulterated liberal voice. Articles that criticized censorship of the arts behind the Iron Curtain were quietly encouraged, and articles that criticized American foreign or domestic policy were quietly discouraged. Stephen Dorril also reveals in his book on MI6 how British agents write articles in magazines under pseudonyms, and discusses articles about the former Yugoslavia published in The Spectator in 1994.

As a result of this, figuring out today which of Encounter’s articles were written with no agenda and which were placed to plant ideas in readers’ minds is a difficult task. Similarly, some articles might have been sincerely meant by their authors, who had no idea of the magazine’s real backers, but were published either because they served as good propaganda, or because they served as good cover for other propaganda to be slipped between.

A good example of this dilemma is the issue of May 1966. It contains articles by, among others, Anthony Burgess, Eugène Ionesco, Robert Graves, Frank Kermode (by then an editor of the magazine), Tom Driberg, Malcolm Muggeridge and John le Carré. It’s an extremely impressive line-up of contributors, but also an intriguing one from a political perspective. Some of these writers might have been used, without their knowledge, by the CIA and MI6—and some might even have been used against the CIA and MI6.

An example of the latter could be Tom Driberg’s article. Driberg was a prominent journalist, Labour MP and later Baron Bradwell. He was also gay, and on visiting Moscow in 1956 to interview the British double agent Guy Burgess, he made the mistake of frequenting a lavatory behind the Metropole Hotel to try to pick up men. The KGB showed him ‘compromising material’ of these photographs, and he was recruited as an agent, codenamed LEPAGE. One of his first acts was the publication of a book on Burgess that claimed he had never spied for the Soviet Union. But Driberg broke off contact with the KGB in 1968, and his very dull 1966 article about Edith Sitwell is not a piece of propaganda for either side in the Cold War. Still, it is intriguing that a Soviet agent of influence was writing articles in an MI6/CIA-fronted magazine.

Another article in this issue was titled ‘Africa Without Tears’. It was written by Rita Hinden, a socialist South African academic at the University of London, in reaction to news of a series of political murders that had recently taken place in Nigeria—murders that turned out to be the firing shots in what would become a lengthy civil war. I don’t know whether Hinden wrote the article directly on the behest of the CIA or MI6, but I think it might well have suited their aims, as she essentially argued why everyone should turn a blind eye to the worsening political situation in Nigeria and, in effect, let them get on with it.

Hinden made this argument in a way that appears extremely heartless with the knowledge of the deaths that resulted in the civil war, but even without hindsight it is an example of the sort of bizarre double-think some intellectuals engaged in at the time. She developed her thesis over several thousand words, but I think a sense of what she was doing can be seen in the callousness of the title, and the article’s final paragraph:

‘As long as we continue to regard Africans as a “special case” to be courted, flattered, excused, expected-greater-things-from, grieved-over, explained-away, we will still not have recognized that they have, once and for all, severed the naval cord which used to bind us. And Africans will continue to regard us with the irritation—merging eventually into pity—which marks the attitude of grown-up children to their anxious, ridiculous parents.’

I’ve read this article many times, because my first novel Free Agent was set in the Nigerian civil war and I discovered a lot about it while researching. The article shocks me every time I read it. Hinden was the editor of another magazine, Socialist Commentary, which reflected the views of the pro-American right wing of the Labour party at the time, and was also involved in the Fabian Society’s journal, Venture, which was funded by the CCF. Michael Josselson described her as a ‘good friend of ours’ and said that the CIA relied heavily on her advice for their African operations.

This article might not have been CIA propaganda, but it was nevertheless CIA-funded, and I think it was propaganda. Its aim was to plant the idea in readers’ minds that post-colonial guilt was the real crime on which they should focus. She argued that a ‘guilt complex’ and ‘emotionalism’ was preventing people from seeing Africa in its proper perspective, and suggested that anyone who felt that Britain had a responsibility to its former colonies was being condescending to Africans—and perhaps even racist. But her claim to respecting Africans was insincere, a pretence that offered readers a convenient excuse for ignoring a growing crisis in a country that, in 1966, had been independent just six years, following 160 years of British rule. It’s not callous to be indifferent to the situation in Nigeria, she argued: it’s treating them as the adults they want to be. It plants some very unpleasant ideas, which were no doubt repeated at dinner parties across England in various forms in May 1966 and after.

The British government did become involved in the war in Nigeria, but mainly as a supplier of arms to the side they thought had the greater chance of winning and continuing their oil contracts following a ceasefire (the federal side). Many in Britain didn’t feel the way Rita Hinden did, and were deeply shocked and moved by the events that took place in Nigeria, and many did something about it. Many Nigerians were irritated by Western involvement but many others weren’t, as lives were saved by organizations such as the International Red Cross, Caritas and others.

Finally, there’s the article by John le Carré, which is perhaps the most intriguing of the lot. In 1966, he was already very much against American foreign policy, and it is hard to imagine a writer less likely to work for the CIA than him. Even unknowingly, his article goes against what both MI6 and the CIA would have liked the magazine’s readers to think, because although it attacks many of the problems in the Soviet Union, he concludes that ‘there is no victory and no virtue in the Cold War, only a condition of human illness and a political misery’.

In February 1966, three months before this issue was published, le Carré had been interviewed on the BBC’s Intimations programme by Malcolm Muggeridge. In that interview, Muggeridge had revealed with a mischievous glint in his eye that he had been a spy during the Second World War. In fact, he was still involved in the espionage world. Le Carré didn’t reveal that he too had been an intelligence officer, and I suspect he had no idea he was then used by MI6 and others in service of an elaborate propaganda operation. The part he played in the operation was tiny: he wrote an article about James Bond.

Did Muggeridge put him up to it? Considering his connections with Encounter, his recent interview with le Carré and his own appearance in the same issue, it seems likely he played a part. In his article, le Carré also expanded on remarks he had made to Muggeridge in the BBC interview about Ian Fleming’s character:

‘I’m not sure that Bond is a spy… I think that it’s a great mistake if one’s talking about espionage literature to include Bond in this category at all. It seems to me that he’s more some kind of international gangster with, as is said, a licence to kill. He’s a man with unlimited movement, but he’s a man entirely out of the political context. It’s of no interest to Bond who, for instance, is president of the United States, or who is president of the Union of Soviet Republics. It’s the consumer goods ethic, really—that everything around you, all the dull things of life, are suddenly animated by this wonderful cachet of espionage: the things on our desks that could explode, our ties which could suddenly take photographs. These give to a drab and material existence a kind of magic which doesn’t otherwise exist.’

The previous year, le Carré had commented in a similar vein to Donald McCormick. In Who’s Who In Spy Fiction. McCormick quoted le Carré as saying that Bond would be ‘the ideal defector’ because ‘if the money was better, the booze freer and women easier over there in Moscow, he’d be off like a shot’.

Titled To Russia, with Greetings, his article in Encounter took the form of an open letter to the editor of Literaturnaya Gazeta, the Soviet Union’s leading literary magazine of the day, concerning an article it had published several months earlier by a V. Voinov reviewing two of his novels, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold and The Looking Glass War. Voinov had argued that, by assuming the role of impartial observer in the Cold War, le Carré was playing a subtler, but more insinuating, game of propaganda than that played by Ian Fleming, and that his fame in the West was a result of readers growing tired of Fleming’s ‘cheap romanticism’. Voinov also alleged that le Carré had been an intelligence agent.

Le Carré ignored the latter charge (which was true), but rebuffed the rest, pointing out that he was not an apologist for the Cold War at all, but opposed to the methods of both sides:

‘In espionage as I have depicted it, Western man sacrifices the individual to defend the individual’s right against the collective. That is Western hypocrisy, and I condemned it because it took us too far into the Communist camp, and too near to the Communist’s evaluation of the individual’s place in society.’

The letter/essay ends with his analysis of Bond:

‘The problem of the Cold War is that, as Auden once wrote, we haunt a ruined century. Behind the little flags we wave, there are old faces weeping, and children mutilated by the fatuous conflicts of preachers. Mr Voinov, I suspect, smelt in my writing the greatest heresy of all: that there is no victory and no virtue in the Cold War, only a condition of human illness and political misery. And so he called me an apologist (he might as well have called Freud a lecher).

James Bond, on the other hand, breaks no such Communist principles. He is the hyena who stalks the capitalist deserts, he is an identifiable antagonist, sustained by capital and kept in good heart by a materialist society; he is a chauvinist, an unblinking patriot who makes espionage exciting, the kind of person in fact who emerges from Lonsdale’s diaries.

Bond on his magic carpet takes us away from moral doubt, banishes perplexity with action, morality with duty. Above all, he has one piece of equipment without which not even his formula would work: an entirely evil enemy. He is on your side, not mine. Now that you have honoured the qualities which created him, it is only a matter of time before you recruit him. Believe me, you have set the stage: the Russian Bond is on his way.’

I discovered this article while browsing in a second-hand bookshop in Rome about a decade ago (and some of the ideas in it influenced me when creating my own character, Paul Dark). But while I find le Carré’s comments on Bond fascinating, I think they address a popular perception of the character, especially as seen in the film adaptations, that isn’t borne out in Ian Fleming’s work. Fleming’s first novel, Casino Royale, published in 1953, is by no means a magic carpet taking us away from moral doubt. Yes, James Bond smokes, drinks and dresses well. But he is also betrayed and tortured, and wracked with doubts about his profession, motivations and more besides. Here is a speech Bond gives in the novel:

‘Take our friend Le Chiffre. It’s simple enough to say he was an evil man, at least it’s simple enough for me because he did evil things to me. If he was here now, I wouldn’t hesitate to kill him, but out of personal revenge and not, I’m afraid, for some high moral reason or for the sake of my country.’

Fleming’s character is a patriot, but as can be seen here he is by no means an unblinking one. And if he were, how would that square with le Carré’s idea that he would defect to Moscow if he thought he could have a better time there?

In this passage and elsewhere, Fleming was influenced by earlier British thriller-writers, notably Geoffrey Household. But he also knew and was a great admirer of Graham Greene, Eric Ambler and Somerset Maugham. The influence of the latter is very clear in his short story Quantum of Solace, published in 1960—one could scarcely get further from the idea of ‘banishing perplexity with action’ than that story.

I think le Carré’s article acted as a lure: it was featured on the cover of the magazine, and his name would have attracted readers. But it also acted as cover, because readers of that article might also have then read, for example, Rita Hinden’s, and been influenced by it.

In his article, le Carré wrote of his own novel, The Spy Who Came In From The Cold:

‘I tried to touch new ground when I discussed the phenomenon of committed men who are committed to nothing but one another and the dreams they collectively evoke. At heart, I said, professional combatants of the Cold War have no ideological involvement. Half the time they are fighting the enemy, a good deal of the time they are fighting rival departments. The source of their energy lies not in the war of ideas but in their own desolate mentalities; they are the tragic ghosts, the unfallen dead of the last war.’

There were, doubtless, a lot of professional combatants who were involved in the Cold War in just this way. But the irony is that, unknown to le Carré, his own words were being used by men who did have an ideological involvement, and who were channeling their energies into the war of ideas.

Secreted in Fiction

I’ve written about the ways in which spy fiction can influence spy fact in The Spies We’ve Loved, but I came across another intriguing example of this when writing my non-fiction book on the Oleg Penkovsky operation, Dead Drop. My research involved interviewing surviving members of the operation, consulting all the available declassified material on it, including debrief transcripts, memoirs, articles and documentaries—and reading spy fiction.

Three novels were particularly helpful. The first was The Russia House by John le Carré, which was loosely based on the operation and which contains several details suggesting inside knowledge of it, perhaps as a result of le Carré’s long friendship with Dickie Franks, who recruited Greville Wynne for MI6 and would later become ‘C’. One snippet, for example, is that the operation in the novel is run from a CIA-funded command centre in London—I discovered in my research that the CIA did fund such a centre, in Pall Mall, but this hadn’t been revealed in any previous literature.

The second spy novel I read was Wages of Treason by Paul Garbler, who was the CIA station chief in Moscow during the operation (its first station chief in the city, in fact), but later came under suspicion of being a traitor in the feverish molehunts of James Jesus Angleton. His novel, self-published in 2004, was an attempt to explain how Angleton had been fooled by a Soviet deception operation into seeing moles where there were none, and also provided some insights into how Penkovsky was handled, and how the CIA worked in Moscow.

The third novel was a Russian one: Julian Semyonov’s TASS Upolnomochen Zaiavit (‘TASS Is Authorized To Announce’), published in 1979, which I had read a few years earlier but which my other research suggested contained incidents that closely echoed the Penkovsky operation. It’s hardly surprising that a Soviet spy novel would draw on one of the most famous operations of the Cold War, just as le Carré had done: in the Soviet Union, Penkovsky was as famous as Kim Philby was in Britain. However, as in The Russia House, some information in the novel wasn’t public knowledge at the time it was published. And one plot point suggested a way that the KGB could have realized the CIA and MI6 were running an agent in Moscow.

Semyonov—whose real surname was Landres—was one of the Soviet Union’s most popular spy novelists. His war-time thriller Semnadtsat mgnoveniy vesny (‘Seventeen Moments of Spring’), was made into the country’s most successful and best-loved television series. In his conversation with Graham Greene (see When Julian Met Graham), Semyonov discussed how Yuri Andropov called him out of the blue in the summer of 1967, shortly after he had been appointed head of the KGB, and asked if he would be interested in being given access to the organisation’s operational archives.

From then on, he told Greene, Andropov had ‘supported him a lot’, although he had occasionally objected to a passage, saying ‘Julian, it is impossible to publish this, because you have bitten us more than Mr Solzhenitsyn!’ On those occasions, instead of cutting his text, Andropov had suggested that Semyonov simply ‘add three lines’ presenting the opposing view: ‘thesis and antithesis’ was the best method. Semyonov told Greene he had never had any problems with censorship as a result, because he simply always added the proverbial three lines presenting the other side of the argument. In another account of this incident, Semyonov said of TASS Is Authorized To Announce: ‘If I asked Mr. Andropov to give me materials, of course he liked my books, and he will give me these materials.’ He also interviewed several KGB officers for the novel.[1]

Having been called by the head of the KGB in this way made for an entertaining anecdote, but the reality must have been at least a little problematic. On the one hand, he was being given an extraordinary opportunity—what spy novelist wouldn’t leap at the chance of being given access to a secret agency’s most classified operational files? On the other hand, even with Andropov’s three lines he would not be free to treat the material however he wished.

His solution was to push the three lines as far as he could. While much of the novel reads like crude propaganda to Western readers today, at times he appears to have been playing a double game. To the KGB and their censors it may have seemed as if he had done precisely what they had wanted him to do, which was to produce an exciting story in which heroic Soviet agents thwarted ruthless imperialist hyenas.

But between the lines, Semyonov smuggled through slivers of satire and criticism of the Soviet system. The wife of one of his protagonists, KGB officer Konstantinov, works as an editor at a publishing house, and he berates her over a manuscript she has asked him to read, calling it a collection of clichés: ‘the bad factory director and the good party organizer, the innovator whom they gagged at first and who in the end gets a medal, the one drunkard in the whole of the workshop… Why do people have to lie so? If there was only one drunkard in ever factory shop, I’d be placing lighted candles in the church! The desire to please—whoever you are trying to please—is a form of insincerity. And then public opinion suddenly realises what is going on, and everyone starts shouting: “Where have all the whitewashers sprung from?”’

It’s mild by modern comparisons, but in 1979, in a novel approved by the head of the KGB and using KGB materials, quite a remarkable thing to have written. He got away with it by balancing it with more obviously ingratiating material. At one point, KGB officer Vitaly Slavin teases undercover CIA officer John Glebb that he would like to make a film:

‘Or not so much make as finish one off. Take From Russia With Love—all I would add is just one more shot! I would put it in just after Bond carried off the coding girl in triumph to London. Just a single line on the screen: “Operation Implant successful. Over to you, Katya Ivanova…’’

This was a crowd-pleasing dig at one of the Soviet Union’s most loathed propaganda figures, James Bond, which also celebrates Russian intelligence’s fondness for maskirovka: deception operations. It is a clever piece of propaganda in itself: an apparent Soviet defeat turned to a cunning victory with a twist at the last moment, MI6’s great triumph revealed as the first stage in a plan to infiltrate a Soviet agent into Britain.

Having warmed the patriotic cockles of his readership, and hopefully had the KGB censors smiling benignly down on his manuscript, Semyonov then added another layer. Konstantinov and his wife visit a film director, Ukhov, who is making a spy thriller. Konstantinov is, on the surface, simply being asked his professional advice as a KGB officer about the authenticity of the film: in reality, there is a more sinister subtext. He is acting as its censor, in just the same way Semyonov’s books, and indeed the films adapted from them, were being overseen by Andropov. Ukhov shows a scene in which his lead actor plays a traitor to the Soviet Union:

‘In the next sequence, the actor tried the role of a spy. Konstantinov immediately reacted against his hunted look: from the very first shot, he conveyed terror and hatred.

“It would be no fun chasing him,’ he observed. “You could see him a mile off!’

“So what? Do you want us to make the enemy heroic?’ Ukhov exclaimed. “They’d have my head!’

“Who?’ Lida asked, placing her hand on her husband’s cold fingers. “Who would have your head?’

“I’m afraid it would be your husband, first and foremost.’

“Nonsense,’ Konstantinov’s face puckered. “If you remember, right through the film I’ve kept emphasizing that your enemies seem naive and stupid. Whereas they have intelligence and talent—that’s right, talent!’

“Can I quote you, when I speak to the Artistic Committee?’

“Don’t bother, I can say it myself. I feel sorry, not so much for the audience as for a talented actor. It’s humiliating to be forced to speak a lie, while making out it’s the truth.’’

Semyonov appears to have discovered an ingenious way of skirting his own Artistic Committee. On the one hand, by having his wise, cultured and noble KGB protagonist point out the foolhardiness of using crude stereotypes, he was laying down a good rule of propaganda: if you make your enemies caricatures, your audience will not be convinced by your arguments, and your efforts will backfire. He was hoping his own censors would see the sense in this and choose to adopt the same line—and in doing so, this would give him greater leeway to insert subtle criticisms of the system. If they objected, he could counter: ‘Do you really want to be like that fool Ukhov, pretending our enemies are all stupid? I thought you might be mature and sensitive enough to realize that such crude propaganda never persuades anyone…’ The tactic apparently worked, as the passage made it into print, although there is also a rather chilling self-awareness in the line that it is humiliating to be ‘forced to speak a lie’.

This novel, then, seems to be propaganda laced with disguised criticism. If so, it was itself a kind of miniature deception operation, carried out by Semyonov against the KGB. Given access to their files on the unspoken understanding that anything he wrote had to be sufficiently flattering, he smuggled a more critical view past Andropov and the censors.

It seems unlikely he was writing with any hope of being read or interpreted this way in the West, but with the benefit of hindsight several details about KGB operational methods in the novel that were let through because they were part of an overall picture painting the intelligence services in a heroic light now suggest a different story, and offer a glimpse into the KGB’s mindset and techniques during the Cold War, and specifically how it might have discovered, and reacted to, the Penkovsky operation.

[1] ‘KGB link adds to author’s intrigue’, Steve Huntley, Chicago Sun-Times, October 13 1987; and ‘In Yulian Semyonov’s Thrillers the Villains Are CIA Types – and Some Say the Author Works for the KGB’, Montgomery Brower, People, April 6 1987.

Spies of Fleet Street

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

In December 1968, the state-controlled Russian newspaper Izvestia ran a series of articles accusing several high-profile British journalists of being spies—listing their names and alleged codenames. The articles caused a storm of protest in Britain: the Russians were claiming journalists and editors at The Sunday Times, The Observer, The Daily Telegraph, The Daily Mail and the BBC worked directly with MI6.

The Soviets’ evidence for all this? A cache of documents they claimed were MI6 memos, and which looked to have been photographed with a miniature spy camera. One showed a table listing each publication, the journalist or editor MI6 had as its contact there, their codename and the codename of their MI6 ‘handler’. Another discussed the procedure for the BBC to broadcast prearranged tunes or sentences that could be used by MI6 officers in the field to prove they were acting on behalf of the British government.

At the time, the claims were dismissed as nonsense by all the newspapers and journalists concerned. The head of the BBC’s External Service—later renamed the World Service—called the articles ‘a fantastic example of secret police propaganda’.

It is true that during the Second World War the BBC had broadcast coded messages to British secret agents behind enemy lines, and that some journalists had worked with MI6 in producing propaganda. But could such activities have really continued into the post-war peacetime period?

When examined by BBC Radio 4’s Document programme, the format, language and tone of the documents all rang true, but establishing whether they were genuine was not simple: MI6 never discusses its operations or declassifies files and all the people named are dead. But a clear consensus emerged among espionage historians and former correspondents contacted by the programme: despite all the denials, the memos were genuine.

‘These are genuine MI6 documents,’ says Stephen Dorril, author of a history of MI6, adding that former MI6 officer Anthony Cavendish had told him before his death that the organisation used journalists in the Cold War.

A clue as to how the Russians got hold of them lay in the date of one of the documents—September 1959. The memos were most likely passed to the Soviets by George Blake, a KGB agent working within MI6, Mr Dorril believes.

At the time, Blake was often the night duty officer at MI6 headquarters in London, and he would roam the corridors with his Minox camera photographing every file he could find, before passing the films to his KGB controller.

Professor Christopher Andrew, MI5’s official historian and an expert in Soviet espionage techniques, suggested an even more intriguing theory. Blake might have originally photographed the documents and passed them over, but the Russians could then have consulted the greatest double agent of all time, Kim Philby, about how they should be used.

Before he had defected to Moscow in 1963, Philby had been under suspicion by MI6 and had been working part-time as a journalist for The Observer and The Economist in Beirut. Philby had been employed at The Observer by the paper’s editor, David Astor—who was one of those named by the Soviet press as an MI6 asset. Mr Astor always denied he was a member of MI6, but the circumstances which led to him being named suggest Philby’s involvement.

‘What Philby was very good at was identifying those things which would be, from the point of view of the British public, the most effective propaganda,’ Professor Andrew said.

Izvestia’s allegations created a brief media storm in the UK in late 1968, but the denials were effective enough that the charges made little impact on how the British public viewed Fleet Street. But at least some of the journalists and editors named by the Russians did have links with MI6.

Phillip Knightley, the Sunday Times journalist, said it was well known among the press pack that his colleague Henry Brandon, who was named by Izvestia, worked for MI6. Mr Knightley also said that one of the others named by the Soviets, The Daily Telegraph’s managing editor Roy Pawley, had arranged journalistic cover for MI6 officers. He said Mr Pawley was ‘notorious’ in Fleet Street for his MI6 connection.

The historian and biographer Sir Alistair Horne also confirmed to Document that he had run three agents for MI6 while working for The Daily Telegraph in Germany in the 1950s, and that Mr Pawley had been aware of his role. ‘A whole new generation has the impression the Cold War wasn’t serious,’ Mr Horne told Document. ‘For those of us who lived through it, it was. We felt we were at war.’

The BBC’s official historian Jean Seaton said the claim that the BBC had broadcast prearranged messages during the post-war period was ‘very plausible’.

The Soviets naturally put the worst slant possible on the memos, but in the main they were telling the truth: during the Cold War, MI6 did have a network of journalists and editors embedded in the British press.

According to Stephen Dorril, the documents offer a rare glimpse into the workings of MI6, and open up a new field of research. ‘We really need to go back and look in detail at some of the key events of the Cold War,’ he says. ‘Look at the newspapers, see what was planted, who were the journalists, and what was it they were trying to put out and say to the British public.’

First published on bbc.co.uk on 3 March 2013

A London Spy Walk

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

‘A South Kensington address is definitely an asset’.

It sounds like an estate agent’s blurb, but it’s actually a secret agent’s. It’s from a report on London written by a Soviet spy in the 1930s, seized by MI5 during the war. The agent recommended South Kensington as a base because it had a good reputation with the police—so furtive-looking men meeting in cafés would be less likely to be questioned.

The whole of Kensington and Chelsea is teeming with espionage locations, in fact. To get a flavour, here’s a quick tour—and don’t forget to check for tails!

First, take the Tube to South Kensington. Head west on Pelham Street and turn left down Old Brompton Road. Take another left at Roland Gardens, turn right to keep on it, and then take a left into Drayton Gardens. If you peek into Holly Mews about halfway down, you’ll find Grove Court. The late-Victorian basement flat at number 18 once belonged to the mother of Kim Philby, the notorious double agent who spied for the KGB while heading up MI6’s anti-Soviet section. In 1955, Philby held a press conference in this flat to gloat over the fact that he had been officially cleared of being ‘the Third Man’. But eight years later the trap finally closed in on him in Beirut, and he fled to Moscow, never to return.

Walk back onto Drayton Gardens and head down to number 102a. In 1941, it was at this address that the poet Stephen Spender and his bride Natasha celebrated their wedding—at the time it was being rented by their friend Cyril Connolly. And the spy connection? The reception was attended by, among others, Philby’s fellow double agent Guy Burgess and the Hungarian-born architect Ernö Golfinger, whose surname Ian Fleming would later appropriate for one of his best-known villains. One can’t help wonder whether Burgess and Goldfinger chatted at the party, about life behind the Iron Curtain, perhaps—or ways to cheat at golf.

Head back down Drayton Gardens. Cross Fulham Road and head all the way down until you reach the King’s Road. Turn left and walk up the King’s Road, past Chelsea Town Hall (a good meeting point according to the 1930s Soviet handbook), until you reach Wellington Square on your right. In Fleming’s novels, James Bond lived in a comfortable flat in a ‘plane-tree’d square’ off the King’s Road. And according to his biographer John Pearson, this is the most likely candidate.

A very short walk from 007 is the address of another famous fictional secret agent: George Smiley. Head back up to the King’s Road and cross over into Bywater Street—John le Carré’s shy but brilliant spy lived at number 9. It’s probably a better location than Bond’s flat, as cul-de-sacs are harder to keep under surveillance.

Now head back up the King’s Road and turn left at Anderson Street. This soon becomes Sloane Avenue, and at number 87 you’ll find Chelsea Cloisters. During the Second World War, this rather posh block of flats was used by the Special Operations Executive to debrief agents on their return from missions overseas. My fictional MI6 agent, Paul Dark, also lives here.

Keep heading up Sloane Avenue and it becomes Pelham Road. Soon we’ll be back at South Kensington Tube, but if the walk has made you hungry or parched, take a right onto Thurloe Square and then a left onto Thurloe Street. At number 20, you’ll find Café Daquise. This cheap, cosy Polish restaurant opened in 1947, and during the Cold War was a stomping ground for Eastern European spies, as well as Christine Keeler, who used to meet here with Yevgeny Ivanov, the senior naval attaché at the Russian Embassy. Savour the atmosphere over some barszcz, round it off with some vodka, and then head up Thurloe Street and back to South Kensington Tube again.

First published in Time Out London, May 2009

Top Ten Spy Gadgets

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

1. Poison-tipped umbrella

Probably the most infamous real-life spy gadget is the umbrella used by the Bulgarian secret services—with KGB help—to kill the dissident writer and broadcaster Georgi Markov. KGB technicians converted the tip of the umbrella into a silenced gun that could fire a pellet containing a lethal dose of ricin. On September 7, 1978, Markov felt himself being jabbed in the thigh as he walked across Waterloo Bridge. A man behind him apologised and stepped into a taxi. Markov died four days later. No arrests have ever been made.

2. Dart gun

It wasn’t just Soviet bloc spies who used such techniques, though. In a 1975 US Senate hearing, CIA Director William Colby handed the committee’s chairman a gun developed by his researchers. Equipped with a telescopic sight, it could accurately fire a tiny dart—tipped with shellfish toxin or cobra venom—up to 250 feet. Colby claimed that this and other weapons had never been used, but couldn’t entirely rule out the possibility.

3. Compass buttons

During the war, the Special Operations Executive—‘Churchill’s secret army’—created a wealth of Q-like devices. One ingenious invention was magnetized trouser buttons, which were to be used for agents who got lost—if they were taken prisoner, for example. By cutting off the buttons and balancing them on each other, they turned into compasses.

4. Exploding briefcase

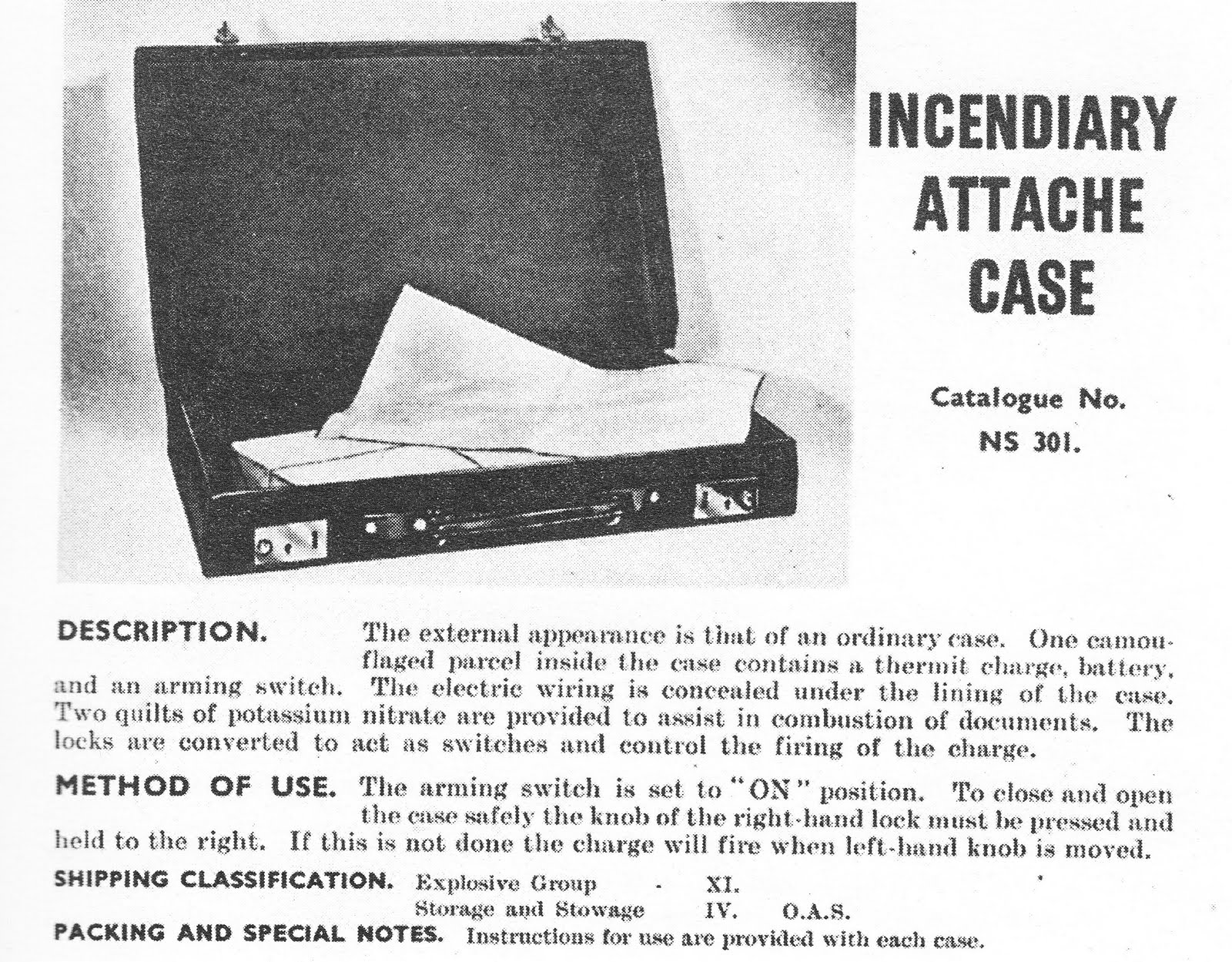

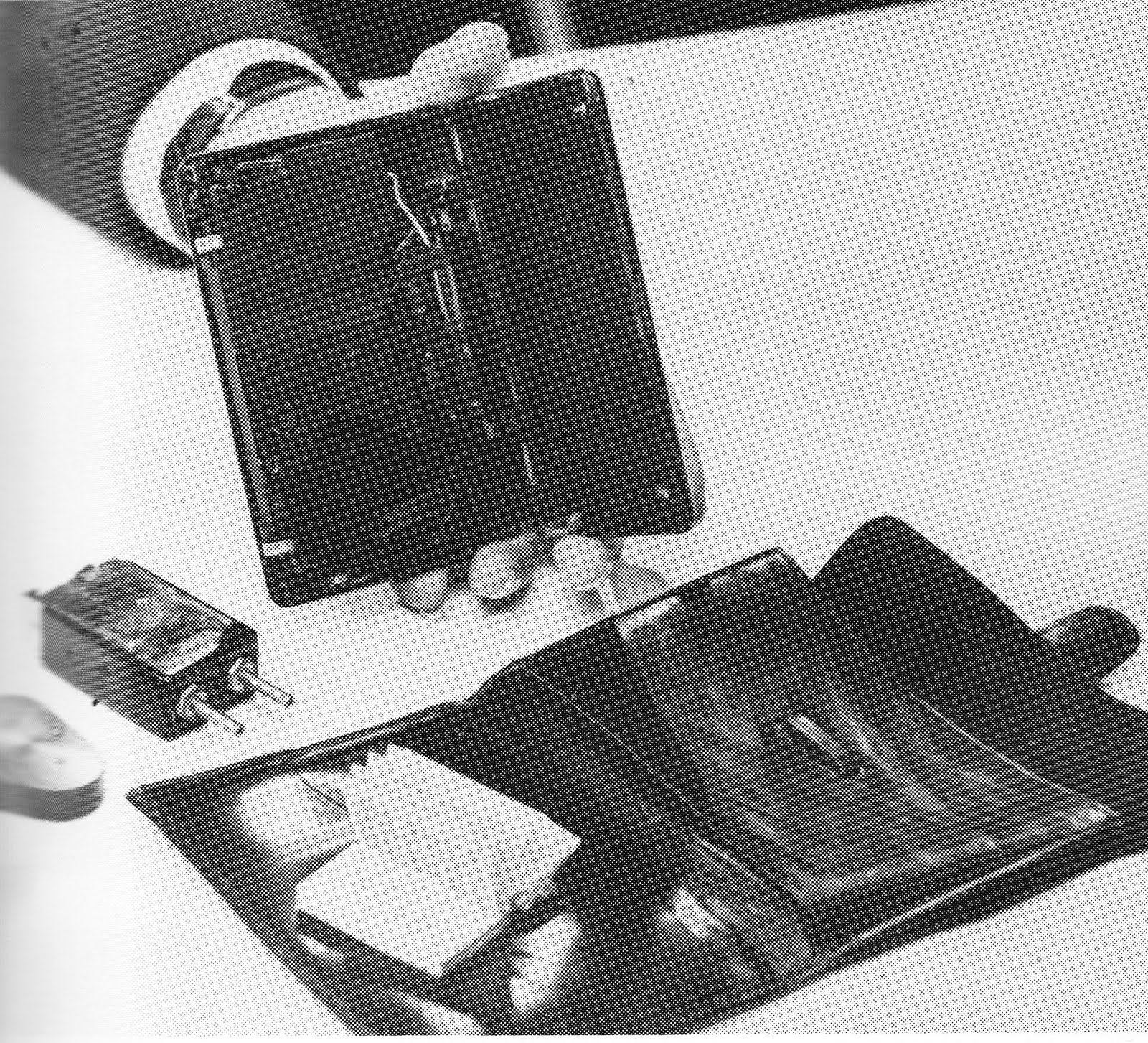

Another SOE invention was a briefcase designed to hold sensitive documents, but which would act as a booby trap for any enemy agent. If the right-hand lock was held down and simultaneously pushed to the right, the case would open safely; otherwise, the left-hand lock would ignite.

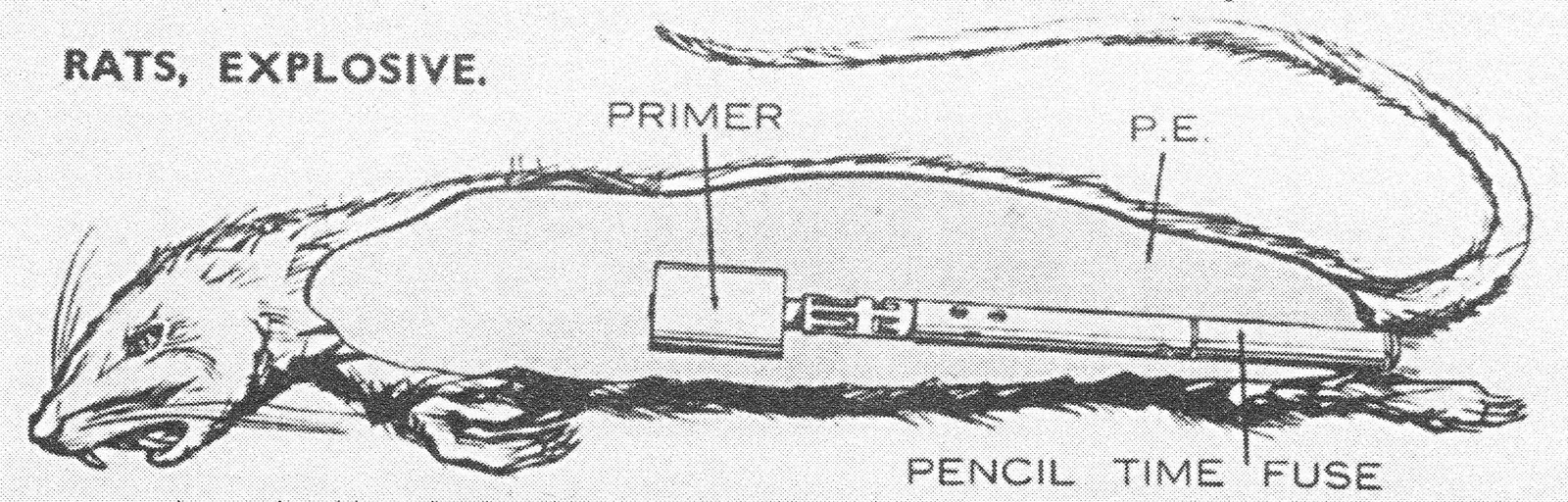

5. Exploding rat