IV. Day and Knight

This article is part of the free ebook Need to Know, which can be read on this website or downloaded here.

Wheatley’s next spy novel was The Quest of Julian Day, published in January 1939. Day’s full name is Hugo Julian du Crow Fernhurst, which outdoes even Swithim Destime, but the character is referred to as Julian Day by most. Day is up against ‘The Big Seven’, a gang led by the occultist Sean O’Kieff. Like Le Chiffre in Casino Royale, he condescendingly calls the hero ‘my dear boy’, apparently one of Crowley’s most-used expressions.[1]

The other members of The Big Seven are revealed to be Lord Gavin Fortescue, the deformed aristocrat of Contraband; Ismail Zakri Bay, an Egyptian; Inosuki Hayashi (‘the Jap’); Azreal Mozinsky, a Polish Jew; Count Emilio Mondragora; and Baron Feldmar von Hentzen. While this sounds very much like a prototypical S.P.E.C.T.R.E., Wheatley was drawing on a long-established fondness in thrillers for sinister organizations like this; they can be found in the work of John Buchan, Sax Rohmer and many earlier writers, among them George Griffith.

With a plot featuring a hunt for treasure in Egypt, The Quest of Julian Day is a straightforward, but rather forced, adventure story. Day is a reasonably capable hero, but not an especially interesting one. He’s very much a return to the gentlemanly tradition: an old Etonian baronet with a double-first from Oxford in Oriental Languages and an expert fencer, he also has a sweet tooth, continually interrupting his mission to find some pralines to nibble.

Wheatley’s fantasies about the espionage world were now being overturned by events in his own life. Maxwell Knight recruited Wheatley’s stepson Bill, an undergraduate at Oxford, to spy on potential fifth columnists among his fellow students, and not long afterwards asked Wheatley himself to help out with his work. The same month as the publication of The Quest of Julian Day, Knight approached him about a young Austrian woman, Friedericka ‘Fritzi’ Gaertner. She had divorced her husband, a German Jew, a few years earlier and in 1938 had come to Britain to visit her sister, who had recently married the brother of Stewart Menzies, who was the deputy head of M.I.6.[2] She had offered to work for British intelligence in return for being allowed to stay in the country.

Knight had become convinced Gaertner would make an excellent agent to infiltrate Nazi-sympathising circles for him, but there was a snag. She needed a work permit to avoid being interned as an enemy alien, and ‘working for M.I.5’ obviously wasn’t feasible. Knight’s first suggestion had been that she get a cover job as ‘a sort of super high-class mannequin’—on meeting her he’d noted that ‘there is no doubt whatever about her very considerable personal attractiveness’—but she wasn’t keen on the idea.[3] Knight now turned to Wheatley: could he not employ her as his secretary/research assistant?

Wheatley interviewed her and, fairly unsurprisingly, was in favour of taking on the attractive young sister-in-law of the deputy head of M.I.6. He wrote to the Ministry of Labour, assuring them that in employing her he wouldn’t be taking work from a British subject; he was planning a new novel set in Central Europe that required a translator with a knowledge of local customs across the region, and he ‘should certainly not be able to employ a British subject in this capacity’.[4] Knight was delighted by Wheatley’s swift response, and wrote to him to say that ‘when you turned your attention to literature the intelligence department lost a great opportunity, though I fear the financial rewards in literature are greater than in the world of intrigue!’[5] Wheatley’s role within the L.C.S. was still 18 months away.

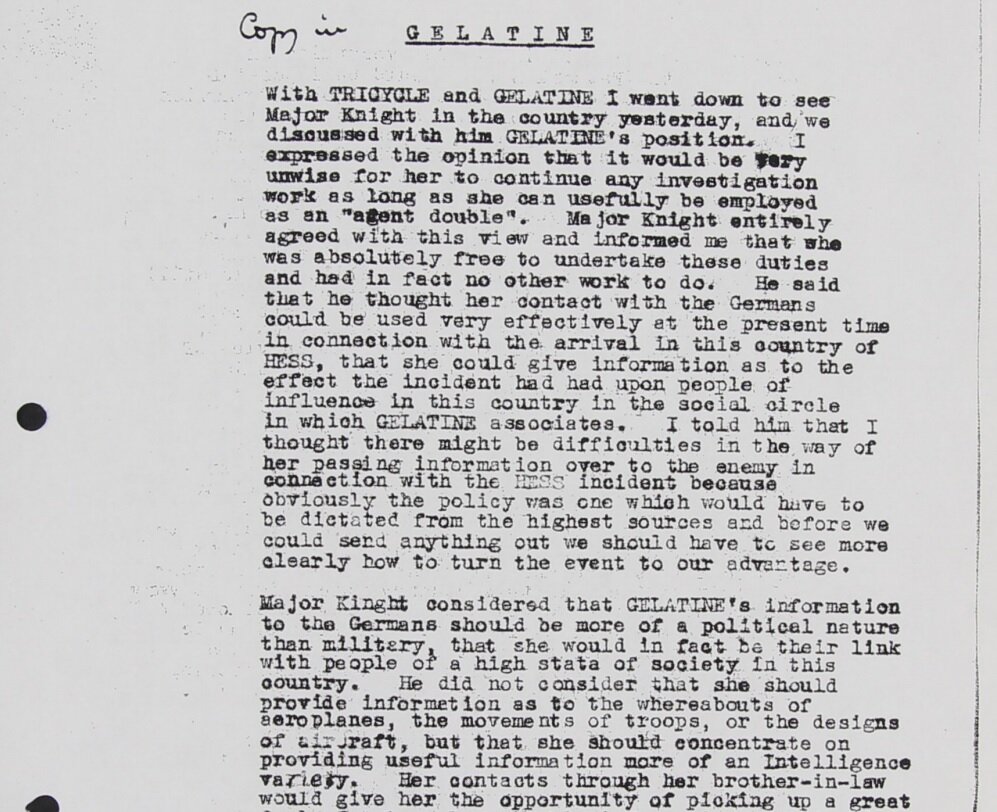

If he didn’t have a plan for a new book at that point, Fritzi Gaertner might well have given him an idea for one. Wheatley prided himself on his research, but while he had visited Germany in 1919, his knowledge of the country under its current regime was, much the same as everyone else’s, gleaned from the newspapers and radio broadcasts, with little hope of improving it from his house in London. Now fate had thrown an intelligent and sympathetic native German-speaker onto his doorstep, giving him the opportunity to get the inside track on a locale few British writers could hope to depict with much authority at this moment: Nazi Germany. Even better than that, Fritzi’s close family connection to the uppermost level of British intelligence gave him a second inside track most thriller-writers would have killed for. For the next few months, her days were kept busy researching and translating information about leading Nazi figures, giving Wheatley ‘invaluable’ material for many novels to come as well as background knowledge he would later put to use in his L.C.S. papers. And by night, Fritzi became M.I.5 agent GELATINE, attending cocktail parties and dinners hosted by pro-Nazi groups such as The Link, reporting back to Knight.[6]

MI5 memorandum concerning agent GELATINE, Friedl Gaertner, 18 May 1941. Source: British National Archives (KV-2-847).

While she was doing that, Wheatley was hard at work, writing Sixty Days To Live, an adventure in a similar vein to Black August, featuring an impending comet hitting the earth and ensuing chaos and martial law. It was published on 24 August 1939, and The Observer recommended it as ‘homeopathic treatment for crisis tensions’.[7] Nevertheless, it was a flop, probably because the title alone was much too grim in the political climate.[8] Eight days following its publication, Germany invaded Poland, and two days after that, Britain was once again at war.

Wheatley didn’t waste any time. While trying to persuade Knight and anyone else who would listen to find him a job in which he could serve, he was feverishly writing his next novel. He already had authentic background material gathered by an Austrian-German M.I.5 agent, and a war to set it in. A story set in Germany now would mean going behind enemy lines, an impossible feat—except perhaps for a secret agent. Another spy story was in order, but a mission into Nazi territory would require someone rougher and tougher than a Swithin Destime or Julian Day. Wheatley decided to return once again to Gregory Sallust. He started writing The Scarlet Impostor on September 6 1939, just three days after Britain declared war, and finished it on October 19. It was published on January 7 1940, making it one of the first spy novels to be set during the Second World War.

‘In view of the importance of your mission, it’s a very special number, TOO... You are now listed by us as Secret Agent No. 1’

It’s also one of the most exciting thrillers of any era, with Sallust jumping from frying pans into fires at every turn across 172,000 words. In Contraband, Sallust had been working in an unofficial capacity for the authorities with the understanding that official backing would be provided if necessary; now British intelligence wants him to make contact with a faction of anti-Nazi generals in Germany, and so he is put on a more formal footing. He’s even allotted a number:

‘“In view of the importance of your mission, it’s a very special number, too; one which has long been vacant and about which there can be no possible mistake. You are now listed by us as Secret Agent No. 1.”

Gregory grinned. “I’m deeply flattered.”’

Wheatley dedicated the novel to Maxwell Knight: ‘My old friend and fellow author, who has often given me good reason to believe that truth really is stranger than fiction’. Knight had become a thriller-writer in 1934, and had dedicated his second novel, Gunman’s Holiday, to Wheatley and his wife. A 1986 biography of Knight was subtitled ‘The Man Who Was M: The Real-life Spymaster Who Inspired Ian Fleming’, although there is little evidence this was the case other than the admittedly striking fact that Knight was known as ‘M’ within M.I.5. Despite being three years younger than Wheatley, he might have been at least part of the inspiration for Gregory Sallust’s white-haired mentor and spymaster, Sir Pellinore Gwaine-Cust. In Arthurian legend, King Pellinore or Pellimore hunts the Questing Beast: Knight was an avid hunter and naturist, later becoming well known as a broadcaster on wildlife, and one obituary described him as ‘a sane and more effective version of kind King Pellinore’ [9]. Coincidence, perhaps, but it would be fitting for a Knight-like mentor to be the agent-runner sending Wheatley’s wish fulfilment figure Sallust on his quests.

~

There is significantly more action in The Scarlet Impostor than Contraband, and Wheatley had to work much harder to make his often-implausible plot developments convince. He did this by supporting the breakneck pacing with a strong degree of verisimilitude regarding the situation in Nazi Germany, thanks to Fritzi Gaertner. One of the novel’s main characters is Erika von Epp, a beautiful German whose Jewish lover has been killed by ‘the brutalities inflicted on him in the concentration-camp at Dachau’. Dachau and the other Nazi concentration camps were not often discussed in Britain this early in the war, but Gaertner would likely have heard about their horrors in some detail. Like Gaertner, Erika’s former lover being Jewish makes her a determined opponent of the Nazi regime, but by the same token her not being currently involved with a Jew means she is able to keep up the pose of being a loyal Nazi in order to gather intelligence for the British.

Providing some relief from the depiction of the horrors taking place inside Germany, the novel also featured Wheatley’s usual insider’s feel for the finer things in life, given added force by his use of real names. Publishers generally required authors to rename any real-life brands they featured, not wishing to provide free advertising. So E. Phillips Oppenheim’s novels featured the Milan Hotel, modelled on the Savoy, and Valentine Williams’ characters smoked Melania cigarettes, a non-existent brand that could only be bought at London’s non-existent Dionysus Club. In Sax Rohmer’s novels, real-life political figures were also disguised, so Hitler became ‘Rudolph Adlon’ and Mussolini ‘Monaghani’. An exception seems to have been cars. Although Leslie Charteris’ Saint drove non-existent Furillacs and Hirondels, and Dornford Yates’ characters favoured the equally fictional Lowland, many other thriller characters drove Rolls Royces, Daimlers, Mercedes-Benzes and Bentleys. Another exception was EF Hornung’s Raffles, who smoked Sullivans, perhaps inspiring Wheatley to do the same (there are several references to Raffles in his novels).

Wheatley took this idea and ran with it—his thrillers were set in the real world, with real people in the midst of real events using real brands. While other writers had dabbled in this sort of ‘product placement’, with The Scarlet Impostor Wheatley became the first to feature it on a grand scale. During the course of his mission, Gregory Sallust smokes Sullivans’ Turkish mixture cigarettes, escapes from pursuing Nazis on a twin-cylinder BMW motorbike and tells a beautiful German aristocrat he hopes to dine with her in the Ritz after the war. He drinks two Bacardis and pineapple juice (his favourite cocktail, we are told), some pre-1914 Mentzendorff Kümmel, a Vermouth Cassis and a few swigs of unspecified brandy, and we learn that his gun is a Mauser automatic and his tailor West’s of Savile Row.

Wheatley integrated many of these details into his plot. When Sallust is in danger of being interned in a concentration camp in Holland for the rest of the war, he sends a message to his chief in London that he knows will be intercepted, asking after an ‘Otto Mentzendorff’. Sir Pellinore immediately recognises the name of the Kümmel they drank together a few weeks earlier and sends Sallust’s former batman Rudd to help him escape. Rudd turns up disguised as an English gent:

‘He was wearing one of Gregory’s smart blue lounge suits with a Sulka tie, Beale and Inman shirt, Scott hat and Lobb shoes—all from Gregory’s wardrobe.’

The tie is later revealed to have a hidden compartment, and in a subsequent novel Sallust’s Beale and Inman shirt stops him from getting shot after a Russian general checks its label to make sure he’s not a Nazi spy. Wheatley used many of these brands himself, and was sprinkling his knowledge into the action to draw readers into a life of luxury, much as he had done when writing catalogues to entice customers as a wine merchant.

Ian Fleming is, of course, famous for using brands in his work in this way. In his 1962 essay How To Write A Thriller, he discussed why such details were irresistible to him:

‘I’m excited by the poetry of things and places, and the pace of my story sometimes suffers while I take the reader by the throat and stuff him with great gobbets of what I consider should interest him, at the same time shaking him furiously and shouting “Like this, damn you!”’[10]

Later in the same essay, he cites the use of real places and things as one of two devices in which a thriller-writer can bring a reader along even when the plot is wildly improbable:

‘First, the speed of narrative, which hustles the reader quickly beyond each danger point of mockery and, secondly the constant use of familiar household names and objects which reassure him that he and the writer have still got their feet on the ground. Real names of things come in useful: a Ronson lighter, a 4½ litre Bentley with an Amherst-Villiers super-charger (please note the solid exactitude), the Ritz Hotel in London. All are points to comfort and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure.’[11]

Fleming, like Wheatley, used this device to reassure readers he still had his feet on the ground, but it was also important that it was rather special ground. This entailed more than simply throwing in lots of well-known brands. In The Scarlet Impostor, Gregory Sallust keeps his Sullivans cigarettes in a ‘plain engine-turned gold case with no monogram or initials’. The simple and unnamed becomes the ultimate brand, its anonymity telling us that this is a man who appreciates a well-crafted object regardless of whether its manufacturer has a reputation. The case is still made of gold, though, and, the crucial telling detail, is ‘engine-turned’—there’s the solid exactitude. The unadorned case also gives added credibility to the special Turkish mixture cigarettes it contains: Sallust doesn’t smoke them for their cachet, but through the same love of good quality. It’s pure coincidence that they’re so exclusive.

Wheatley used this technique to great effect in The Scarlet Impostor. In the second half of the novel, Sallust arrives in Paris searching for members of a Communist anti-Nazi cell:

‘Whenever he stayed in the French capital he put up at the St Regis, in the Rue Jean Goujon, just off the Champs Elysées. It was a quiet hotel and Gregory preferred it to the larger places, although it was quite as expensive, because each of the rooms was furnished with individual pieces. Many of them were valuable antiques, giving the place the atmosphere of a beautifully furnished private house rather than of an hotel, and Gregory liked luxury and comfort whenever he could get it.’

Moments of luxury and comfort have been mainstays in the lives of fictional secret agents since the birth of the thriller, but Wheatley knew that the devil was in the details, and took the convention much further than previously. After checking into the St Regis, Sallust’s mission ‘requires’ him to woo a beautiful young Frenchwoman, Collette. He’s not sure where to take her to dinner. After considering and rejecting the Tour d’Argent, the Café de Paris and Pocardi’s for varying reasons, he remembers the Vert Galant, ‘down by the river on the right bank’:

‘Quiet and unostentatious, it was yet one of the oldest-established restaurants in Paris, and the cooking there was excellent.’

Collette approves of his choice:

‘Real French cooking—not the sort of messed-up things they make for you English and the Americans in the smart places—so I have been told. I have never been there and I’d love to go, but I’m afraid you will find it very expensive.’

What’s the purpose of this for readers in a fast-paced thriller? We are being shown that Sallust is not simply a man of means (although he is that, too), but that he has a connoisseur’s tastes—and in 1940 as today, knowing the place beloved by the locals is the ultimate insider one-upmanship. We can trust Sallust as a guide to this sort of lifestyle, and perhaps imagine ourselves in his shoes. One day, if we visit Paris, we might follow in his footsteps and not make any schoolboy errors by taking attractive young women to overly ostentatious restaurants.

In the short story From A View To A Kill, published two decades later, Ian Fleming upped the ante on this device even further. In Paris, we learn, Bond doesn’t stay in a lesser known but nevertheless expensive hotel like the St Regis: no, he stays in the Terminus Nord, ‘because he liked station hotels and because this was the least pretentious and anonymous of them’. And, as in Wheatley, the restaurants Bond chooses to dine in are never the obvious ones:

‘For dinner, Bond went to one of the great restaurants—Véfour, the Caneton, Lucas-Carton or the Cochon d’Or. These he considered, whatever Michelin might say about the Tour d’Argent, Maxims and the like, to have somehow avoided the tarnish of the expense account and the dollar.’

This is one of those ‘points to comfort and reassure the reader on his journey into fantastic adventure’, but it also reveals character. Fleming used ‘the real names of things’ to show Bond’s inner self. From A View To A Kill also features a long description of Bond in a Parisian café:

‘James Bond had his first drink of the evening at Fouquet’s. It was not a solid drink. One cannot drink seriously in French cafés. Out of doors on a pavement in the sun is no place for vodka or whisky or gin. A fine à l’eau is fairly serious, but it intoxicates without tasting very good. A quart de champagne or a champagne à l’orange is all right before luncheon, but in the evening one quart leads to another quart and a bottle of indifferent champagne is a bad foundation for the night. Pernod is possible, but it should be drunk in company, and anyway Bond had never liked the stuff because its liquorice taste reminded him of his childhood. No, in cafes you have to drink the least offensive of the musical comedy drinks that go with them, and Bond always had the same thing—an Americano—Bitter Campari, Cinzano, a large slice of lemon peel and soda. For the soda he always stipulated Perrier, for in his opinion expensive soda water was the cheapest way to improve a poor drink.’

This might appear aimless, but by giving his character forceful, unexpected and intriguing feelings about such an apparently trivial matter as ordering a drink, Fleming brings it to life and puts it centre-stage: this is not a trivial matter to James Bond. This, as Fleming put it, is ‘the poetry of things’. It's not simply a scene in which a character decides what to drink at a Paris café, but a statement of intent, a philosophy, a weighted moment.

Fleming was not simply interested in brands, but in an attitude towards them. They are sometimes very strong attitudes: Bond knows the best cafés in Paris and knows a lot about drinks, so much so that he’s a close-to-insufferable snob about them. He condescends to have a ‘musical comedy drink’ in a famous Paris bar. He doesn’t care what Michelin says about Maxim’s—he knows what he feels about it, and that’s what matters. He doesn’t follow the crowd or parrot advertisements and tourist guides, but makes up his own mind about what is the best or most sophisticated option. He has utter faith in his own taste, and as readers we are invited to do the same. Fleming’s use of real names and places didn’t simply hustle readers past improbabilities in his plots, but established a crucial part of Bond’s character: that he is his own man. Bond brands everything around him with his own taste.

The first germs of all this can be seen in The Scarlet Impostor.

~

The novel was a turning point for Wheatley, who had been trying for several years to create a hero in the vein of Raffles, Bulldog Drummond and the Saint. Like those three characters, Sallust is a ‘bad hat’ with vigilante tendencies. But he is also on the right side of the law, a secret agent working in Britain’s interests. He has the courage and duty to country of Richard Hannay and the streak of hedonism and decadence of Simon Templar, but a fondness for ungentlemanly behaviour that would have outraged both. Despite the focus on luxury and the nod to Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel in its title, The Scarlet Impostor has a much more violent tone than most of its antecedents. In this novel, Wheatley introduced Gruppenführer Grauber, who plans to drop our hero into an acid bath; he would become Sallust’s arch-enemy as the series progressed. Sallust himself is recognisably the same character as from Contraband, a suave, hedonistic, resourceful secret agent, but his brutality is more pronounced:

‘Before the Nazi could open his mouth Gregory’s left hand shot out, caught him by the throat and, swinging him round, forced him back against the wall. With complete ruthlessness Gregory raised his right fist and smashed it into the little man’s face.

As his head was jammed against the wall he caught the full force of the blow. A gurgling moan issued from his gaping mouth, but Gregory knew that his own life depended upon putting the wretched man out, and with pitiless persistence he hammered the German’s face with his right fist, banging his head against the wall with each blow until it began to roll about on his shoulders and Gregory knew that he had lost consciousness.’

The world was now at war, and this novel was the direct product of it: Gregory Sallust wasn’t in favour of playing cricket against his enemies any more than his creator.

Wheatley hadn’t set out to make Sallust a series character, but he would prove so popular (several books in the series sold over a million copies) that he ended up writing more adventures for him than he’d foreseen. In doing so, he created a new kind of secret agent character: as debonair and patriotic as the clubland heroes who had come before, but significantly more sexually active, violent and morally ambivalent. Among the first to follow in the footsteps of The Scarlet Impostor’s success was his old friend Peter Cheyney: June 1942 saw the publication of his novel Dark Duet, the first in a new series featuring a secret unit of sophisticated but brutal British agents who kill suspected Nazis wherever they find them.

In the next novel in Wheatley’s series, Faked Passports, published in June 1940, Sallust travels to the Arctic Circle. We are given the most complete description of the character to date, learning that he is in his late thirties, ‘dark, lean-faced’ with ‘smiling eyes and a cynical twist to his firm, strong mouth.’ After taking a hit to the back of his head with a spent bullet near Petsamo, he loses his memory. In and of itself, this is not a particularly unusual plot device, but amnesia has an unusual effect on Gregory Sallust, as his girlfriend, the Countess von Osterberg, reflects:

‘In those hectic days they had spent in Munich and Berlin together early in November they had been the most passionate lovers. When they had met again in Helsinki his absence from her had seemed only to have increased his eagerness; but their opportunities for love-making had been lamentably few. Then his injury at Petsamo had changed his mentality in that respect as in all others. On waking on their first morning in the trapper’s house he had accepted quite naturally that he was in love with her, but it had been an entirely different kind of love. He was tender and thoughtful for her and followed her every movement with almost dog-like devotion, but he did not seem to know even the first steps in physical love-making any more.

Erika had known the love of many men but to be treated as a saint and placed upon a pedestal was an entirely new experience to her and she had thoroughly enjoyed it. There was something wonderfully refreshing in Gregory’s shy, boyish attempts to hold her hand or steal a kiss on the back of her neck when the others were not looking; and she had known that at any moment she chose she could reawake his passions…’

This is strong stuff for a novel published in 1940, with broad hints at both pre-marital sex (the pair would not wed until They Used Dark Forces, published in 1964) and promiscuity. But the most striking thing about it is its similarity with the closing scenes of Fleming’s You Only Live Twice, in which James Bond also loses his memory and in doing so becomes an innocent regarding ‘physical love-making’.[12]

The eponymous villain of The Black Baroness, published in October 1940, is a middle-aged Frenchwoman with a ‘dead white face’ and jet-black eyes and hair who acts as ‘Hitler’s great whore mistress’. Using her position in society, she discovers the types of women senior military figures in Allied and neutral states are attracted to and gives instructions to the Gestapo, who consult their ‘list of beautiful harpies’ and send the appropriate matches to her; she then sets them to seduce their intended victims. Sallust meets one of these women, Paula von Steinmetz, who naturally tries to seduce him, but he fends her off by pretending he isn’t man enough for her:

‘“The sort of man you want is a chap who’d treat you rough and give you a beating if you played him up.”

“Mein Gott, nein!” Paula protested quickly.

“Oh yes, you do,” Gregory assured her. “Every woman does. I don’t mean a drunken blackguard or anything of that kind, but a chap with a will of his own who wouldn’t stand any nonsense and if he saw you flashing those lovely eyes of yours at anybody else would take you home and give you a good spanking.”

Paula’s colour deepened a little under her make-up and Gregory knew that he had judged her rightly. She was a strong, highly-sexed young woman who would thoroughly enjoy occasional rows with her lovers and derive tremendous kick from a mild beating-up in which she was finally possessed forcibly, so that her sobs of anger gave way almost imperceptibly to gasps of passionate emotion.

“Well,” she admitted slowly, “if one loves a man one naturally expects him to assert himself at times, otherwise how can one possibly respect him?”’

The irony, of course, is that Sallust is precisely the sort of man he is describing, as is made clear elsewhere in the series. This would find an echo in the infamously disturbing passage in Casino Royale in which Bond fantasises about Vesper in a very Sallust way:

‘He felt the bruises on the back of his head and on his right shoulder. He reflected cheerfully how narrowly he had twice that day escaped being murdered. Would he have to sit up all that night and wait for them to come again, or was Le Chiffre even now on his way to Le Havre or Bordeaux to pick up a boat for some corner of the world where he could escape the eyes and the guns of Smersh?

Bond shrugged his shoulders. Sufficient unto that day had been its evil. He gazed for a moment into the mirror and wondered about Vesper’s morals. He wanted her cold and arrogant body. He wanted to see tears and desire in her remote blue eyes and to take the ropes of her black hair in his hands and bend her long body back under his. Bond’s eyes narrowed and his face in the mirror looked back at him with hunger.’

Towards the end of The Black Baroness, Gregory Sallust meets the baroness herself, who takes the opportunity to poison his wine. Sallust is pinned to his chair, paralysed, and the villain, in the traditional style, calmly discusses his imminent death:

‘“Good-bye, Mr. Sallust; you will die quite peacefully and in no great pain.”’

She is proven wrong, naturally: Sallust is rushed to a doctor and soon recovers. In From Russia, With Love, published in 1957, James Bond would also be poisoned by an older female villain with a penchant for pimping out beautiful young women to extract information from the enemy, although it comes not in a glass of wine but from a dagger concealed in Rosa Klebb’s boot.

After The Black Baroness, Wheatley left Sallust again to write a standalone thriller, Strange Conflict, published in 1941. This, too, seems to have been on Ian Fleming’s radar. It features a privileged group of British and American agents trying to discover how the Nazis are predicting the routes of the Atlantic convoys. The trail leads to Haiti, but before the group even arrive on the island they are attacked by sharks. They are saved by a Panama-hatted Haitian called Doctor Saturday, who puts them up at his house and then takes them to a Voodoo ceremony, where they witness a sacrifice to Dambala. Two women wearing black are shooed away by the priest; one of the group asks Doctor Saturday why:

‘He replied in his broken French that they were in mourning and therefore had no right to attend a Dambala ceremony, which was for the living. Their association with recent death caused them to carry with them, wherever they went, the presence of the dreaded Baron Samedi.

“Lord Saturday,” whispered Marie Lou to the Duke. “What a queer name for a god!” But the Doctor had caught what she had said and turned to smile at her.

“It is another name that they use for Baron Cimeterre. You see, his Holy Day is Saturday. And it is a sort of joke, of which the people never get tired, that my name, too, is Saturday.”’

It is, of course, not a joke at all: Doctor Saturday, they soon discover, is the physical incarnation of Baron Samedi, and the villain they have been trying to track down. In Live and Let Die, published 13 years later, Ian Fleming featured a villain with the same name transplanted to Jamaica, where he wrote all his books. In that novel, Samedi is revealed to be a front for a black American gangster known as Mr. Big, as Bond learns from his assistant Solitaire:

‘“You’re thinking I shan’t understand,” he said. “And you’re right up to a point. But I know what fear can do to people and I know that fear can be caused by many things. I’ve read most of the books on Voodoo and I believe that it works. I don’t think it would work on me because I stopped being afraid of the dark when I was a child and I’m not a good subject for suggestion or hypnotism. But I know the jargon and you needn’t think I shall laugh at it. The scientists and doctors who wrote the books don’t laugh at it.”

Solitaire smiled. “All right,” she said. “Then all I need tell you is that they believe The Big Man is the Zombie of Baron Samedi. Zombies are bad enough by themselves. They're animated corpses that have been made to rise from the dead and obey the commands of the person who controls them. Baron Samedi is the most dreadful spirit in the whole of Voodooism. He is the spirit of darkness and death. So for Baron Samedi to be in control of his own Zombie is a very dreadful conception. You know what Mr. Big looks like. He is huge and grey and he has great psychic power. It is not difficult for a negro to believe that he is a Zombie and a very bad one at that. The step to Baron Samedi is simple. Mr. Big encourages the idea by having the Baron's fetish at his elbow.”’

Mr. Big is exploiting a fear of the supernatural to quell the island’s believers, an idea Fleming would re-use in Dr No four years later, but this is also the only Bond story to take a leaf out of Wheatley’s books and treat the occult as a real force: James Bond believes voodoo works, and we as readers are also asked to accept the supernatural. Solitaire could be mistaken in her belief in Mr. Big’s ‘great psychic power’, but she appears to be genuinely telepathic herself.